Informatics Educational Institutions & Programs

The Ludwigslied (in English, Lay or Song of Ludwig) is an Old High German (OHG) poem of 59 rhyming couplets, celebrating the victory of the Frankish army, led by Louis III of France, over Danish (Viking) raiders at the Battle of Saucourt-en-Vimeu on 3 August 881.

The poem is thoroughly Christian in ethos. It presents the Viking raids as a punishment from God: He caused the Northmen to come across the sea to remind the Frankish people of their sins, and inspired Louis to ride to the aid of his people. Louis praises God both before and after the battle.[1]

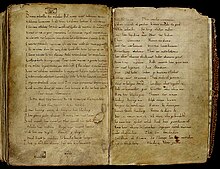

The poem is preserved over four pages in a single 9th-century manuscript formerly in the abbey of Saint-Amand, now in the Bibliothèque municipale, Valenciennes (Codex 150, f. 141v–143r). In the same manuscript, and written by the same scribe, is the Old French Sequence of Saint Eulalia.[2]

The poem speaks of Louis in the present tense: it opens, "I know a king called Ludwig who willingly serves God. I know he will reward him for it". Since Louis died in August the next year, the poem must have been written within a year of the battle. However, in the manuscript, the poem is headed by the Latin rubric Rithmus teutonicus de piae memoriae Hluduico rege filio Hluduici aeq; regis ("German song to the beloved memory of King Louis, son of Louis, also king"), which means it must be a copy of an earlier text.[3]

Synopsis

Dennis Green summarises the poem as follows:

After a general introductory formula in which the poet claims to know of King Ludwig (thereby implying the reliability of what he has to say) this king’s prehistory is briefly sketched: the loss of his father at an early age, his adoption by God for his upbringing, his enthronement by divine authority as ruler of the Franks, and the sharing of his kingdom with his brother Karlmann. [ll. 1–8]

After these succinct eight lines the narrative action starts with God’s testing of the young ruler in sending the Northmen across the sea to attack the Franks as a punishment for their sinfulness, who are thereby prompted to mend their ways by due penance. [ll. 9–18] The kingdom is in disarray not merely because of the Viking aggression, but more particularly because of Ludwig's absence, who is accordingly ordered by God to return and do battle. [ll. 19–26]

Raising his war-banner Ludwig returns to the Franks, who greet him with acclamation as one for whom they have long been waiting. Ludwig holds a council of war with his battle-companions, the powerful ones in his realm, and with the promise of reward encourages them to follow him into battle. [ll 27–41] He sets out, discovers the whereabouts of the enemy and, after a Christian battle-song, joins battle, which is described briefly, but in noticeably more stirring terms. Victory is won, not least thanks to Ludwig’s inborn bravery. [ll. 42-54]

The poem closes with thanks to God and the saints for having granted Ludwig victory in battle, with praise of the king himself and with a prayer for God to preserve him in grace. [ll. 55–59][4]

Genre

Although the poem is Christian in content, and the use of rhyme reflects Christian rather than pagan Germanic poetry, it is often assigned to the genre of Preislied, a song in praise of a warrior, of a type which is presumed to have been common in Germanic oral tradition[5][6] and is well-attested in attested in Old Norse verse.[7] Not all scholars agree, however.[8] Other Carolingian-era Latin encomia are known for King Pippin of Italy (796)[a] and the Emperor Louis II (871),[b] and the rhyming form may have been inspired by the same form in Otfrid of Weissenburg's Evangelienbuch (Gospel Book), finished before 871.[6][9]

Language and authorship

There is a consensus that the OHG dialect of the Ludwigslied is Rhine Franconian.[10] However, this was a Rhineland dialect from the area around Mainz in East Francia, remote from from St Amand and Ludwig's kingdom.[11] Thus there is an apparent inconsistency between the language of the text on the one hand and the origin of the manuscript and the event described on the other.[12][13]

However, the language also shows some features which derive from the German dialects closest to Saucourt, Central Franconian and Low Franconian.[14][15] Additionally, the prothetic h before initial vowels (e.g. heigun (l.24) for correct eigun, "have") indicates interference from the Romance dialect.[16] The fact that the scribe was bilingual in French and German is also locates the text away from the Rhine Franconian area.

Taken together, this evidence suggests that the text was written in an area close to the linguistic border between Romance and Germanic. Bischoff's localising of the script to an unidentified known scriptorium Lower Lotharingia on the left bank of the Rhine stregthens this conclusion.[17]

However, it is impossible to tell on purely linguistic grounds whether these local indications belong to the original text or arose only in local copying. A number of solutions have been suggested:

- the original text was written in East Francia and the other dialect features were introduced when the text was copied in West Francia by a locally educated, bilingual scribe;[12]

- it was composed in West Francia by someone who either came from East Francia or had been educated there, but his language was affected by features from the local Frankish dialects and the Romace idiom of the area.[12]

- while the general population of the area round Saucourt and St Amand spoke the local Romance dialect (Picard-Walloon), in court circles there was widespread French-German bilingualism amongst both senior clergy and aristocracy.[18][19] Many nobles had connections with East Francia, and a local Frankish dialect, often referred to as West Frankish (Westfränkisch), may have been spoken at Ludwig's court.[16][20]

The first of these options seems implausible: God gives Ludwig "a throne here in Francia" (Stuol hier in Vrankōn, l. 6), which only makes sense from a Western perspective.[12] The personal commitment of the author to Ludwig ("I know a king", Einan kuning uueiz ih, l. 1) also indicates that he was a close to Ludwig's court rather than an outsider.

Manuscript

Description

The Ludwigslied is preserved over four pages in a single 9th-century manuscript formerly in the monastery of Saint-Amand, now in the Bibliothèque Municipale, Valenciennes (Codex 150, fol. 141v-143r). [2]

-

Fol. 141v, bottom

(ll. 1–7). -

Fol. 142r

(ll. 8–31). -

Fol. 142v

(ll. 32–55). -

Fol. 143r, top,

(ll. 56–59).

The codex itself dates from the early 9th century and originally contained only works by Gregory of Nazianzus in the Latin translation by Tyrannius Rufinus (fol. 1v-140r). The blank leaves at the end of the codex contain later additions in four different hands:[21][22][23]

- Dominus celi rex et conditor, a sequence in Latin (fol. 140v to 141r)

- Cantica uirginis eulalie, a 14-line sequence about Saint Eulalia in Latin (fol. 141r)

- the Sequence of Saint Eulalia in Old French (fol. 141v)

- the Ludwigslied (fol. 141v to 143r)

- Uis fidei tanta est quae germine prodit amoris, 15 couplets in Latin (fol. 143r to 143v).

The Sequence of Saint Eulalia and the Ludwigslied are written in the same hand. A Carolingian minuscule with rustic capitals for the rubric and first letter of each line, it differs from the other hands in the manuscript.[24] The text of the Ludwigslied is presumed to be a copy made after August 882 as the poem describes a living king, while the rubric refers to Ludwig as being "of blessed memory" (Latin: piae memoriae).[25]

Sources

St Amand's ownership of the codex is indicated by the note liber sancti amandi ("St Amand's book") on the verso of the final folio (143), but this dates from the twelfth century,[26] and the long-held view that the text of the Ludwigslied was written in St Amand itself now seems unlikely to be correct. The hand of the Sequence of Saint Eulalia and the Ludwigslied does not show the characteristics of the scriptorium of St Amand, and the limp binding is untypical of the library.[27]

The MS was unlikely to have been at St Amand before 883, when the abbey and its library were destroyed by Viking raiders. The monks returned after a few years[28] and the library's holdings were rebuilt from 886 onwards under Abbot Hucbald. Hucbald himself provided 18 volumes, and further volumes seem to have been "scrounged" from around the region.[29] MS 150 is likely to have been among these new accessions.[25][30]

Rediscovery

In 1672 the manuscript was discovered in St Amand by the Benedictine monk Jean Mabillon, who commissioned a transcription, though, unfamiliar with Old High German, he was unable to appreciate its shortcomings (Willems later counted 125 errors).[31] He forwarded this to the Strassburg jurist and antiquarian Johann Schilter. WHen he asked for a better transcription, the manuscript could no longer be found, presumably having gone astray when the abbey was hit by an earthquake in 1692. Schilter published the transcription in 1696 with a Latin translation, "together with an expression of his misgivings".[32] (Mabillon published his own version in 1706.)[33] Subsequent editions by Herder (1779), Bodmer (1780), and Lachmann (1825) were necessarily based on Mabillon's text, though attempts were made to identify and correct likely errors.[34][26]

In 1837 Hoffman von Fallersleben set out to trace the fate of the manuscript, which he discovered, uncatalogued, in the Valenciennes library. He immediately made and published a new transcription, along with the first transcription of the Sequence of Saint Eulalia, with a commentary by Jan Frans Willems.[35] It was Jacob Grimm who in 1856 gave it the title of Ludwigslied.[36][37]

Excerpt

The first four lines of the poem, with an English translation.

| Old High German [38] | English translation[39] |

|---|---|

Einan kuning uueiz ih, || Heizsit her Hluduig, |

I know a king — his name is Hluduig — |

Notes

- ^ Bostock, King & McLintock 1976, p. 241.

- ^ a b Handschriftencensus 2024.

- ^ Harvey 1945, p. 7.

- ^ Green 2002, pp. 282–283. Line numbers added.

- ^ Bostock, King & McLintock 1976, pp. 242–244.

- ^ a b Freytag 1985, col. 1038.

- ^ Marold 2001.

- ^ Green 2002, p. 294: "There are reasons to doubt whether it is justified to see [the] poem in terms of the Germanic past ... the more so since the Germanic praise-song, although attested in the North, is a hypothetical entity for southern Germania. The Ludwigslied is of course a song of praise, ... but poetic euologies are common ... in Latin as well as various vernaculars, without there being a trace of justification to identify them with the specifically Germanic Preislied. Interpreting the poem in terms of a postulated literary genre of the past ... has led inevitably to wishful thinking".

- ^ Bostock, King & McLintock 1976, p. 247.

- ^ Harvey 1945, p. 12, "that the main dialect of the poem is Rhenish Franconian has never been called into question."

- ^ Schützeichel 1966–1967, p. 298.

- ^ a b c d Harvey 1945, p. 6.

- ^ Hellgardt 1996, p. 24.

- ^ Schützeichel 1966–1967, p. 300.

- ^ Freytag 1985, col. 1037.

- ^ a b Bostock, King & McLintock 1976, p. 246.

- ^ Bischoff 1971, p. 132, "ein anderes wohl kaum mehr bestimmbares Zentrum des linksrheinischen, niederlothringischen Gebiets."

- ^ Harvey 1945, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Hellgardt 1996.

- ^ Schützeichel 1966–1967.

- ^ Bauschke 2006, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Groseclose & Murdoch 1976, p. 67.

- ^ von Steinmeyer 1916, p. 87.

- ^ Fischer 1966, p. 25*.

- ^ a b Horváth 2014, p. 5.

- ^ a b Herweg 2013, p. 242.

- ^ Bischoff 1971, p. 132 (and fn. 131).

- ^ Platelle 1961, p. 129, "la communauté revint sur place peu après le second raid, soit après une absence de trois ou quatre années environ".

- ^ Platelle 1961, p. 129, quoting André Boutemy, "grappilés un peu partout".

- ^ Schneider 2003, p. 294.

- ^ Hoffmann von Fallersleben & Willems 1837, p. 25.

- ^ Chambers 1946, p. 448.

- ^ Mabillon 1706.

- ^ Hoffmann von Fallersleben & Willems 1837, p. 33.

- ^ Hoffmann von Fallersleben & Willems 1837.

- ^ Schneider 2003, p. 296.

- ^ Grimm 1856.

- ^ Braune & Ebbinghaus 1994.

- ^ Bostock, King & McLintock 1976, p. 239.

Editions

- Schilter, J (1696). Ἐπινίκιον. Rhythmo teutonico Ludovico regi acclamatum, cum Nortmannos an. DCCCLXXXIII. vicisset. Strassburg: Johann Reinhold Dulssecker. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- Mabillon, Jean (1706). Annales ordinis S. Benedicti occidentalium monachorum patriarchae... Vol. III. Paris: Charles Robustel. pp. 684–686. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- Hoffmann von Fallersleben, August Heinrich; Willems, J F (1837). Elnonensia. Monuments des langues romane et tudesque dans le IXe siècle, contenus dans un manuscrit de l'Abbaye de St.-Amand... Ghent: Gyselynck. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- von Steinmeyer, Emil Elias, ed. (1916). "XVI. Das Ludwigslied". Die kleineren althochdeutschen Sprachdenkmäler. Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung. pp. 85–88. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- Braune, Wilhelm; Ebbinghaus, Ernst A., eds. (1994). "XXXVI. Das Ludwigslied". Althochdeutsches Lesebuch (17th ed.). Tübingen: Niemeyer. pp. 84–85. doi:10.1515/9783110911824.136b. ISBN 3-484-10707-3. The standard edition of the text.

Bibliography

- Bauschke, Ricarda (2006). "Die gemeinsame Überlieferung von 'Ludwigslied' und 'Eulalia-Sequenz'". In Lutz, E C; Haubrichs, W; Ridder, K (eds.). Text und Text in lateinischer und volkssprachiger Überlieferung des Mittelalters. Wolfram Studien. Vol. XIX. Berlin: Erich Schmidt. pp. 209–232. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- Bischoff, Bernhard (1971). "Paläographische Fragen deutscher Denkmäler der Karolingerzeit". Frühmittelalterliche Studien. 5 (1): 101–134. doi:10.1515/9783110242058.101.

- Bostock, J. Knight; King, K. C.; McLintock, D. R. (1976). A Handbook on Old High German Literature (2nd ed.). Oxford: The Clarendon Press. pp. 235–248. ISBN 0-19-815392-9. Retrieved 12 March 2024. Includes a translation into English. Limited preview at Google Books

- Chambers, W W (1946). "Rhythmus Teutonicus ou Ludwigslied? by Paul Lefrancq". Modern Language Review. 41 (4): 447–448. Retrieved 10 March 2024. (Review)

- Fischer, Hanns, ed. (1966). "Ludwigslied". Schrifttafeln zum althochdeutschen Lesebuch,. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. p. 25*. doi:10.1515/9783110952018.49a.

- Fouracre, Paul (1985). "The Context of the Old High German Ludwigslied". Medium Aevum. 54 (q): 87–103. doi:10.2307/43628867. JSTOR 43628867.

- ———— (1989). "Using the Background to the Ludwigslied: Some Methodological Problems". In Flood, John L; Yeandle, David N (eds.). "'Mit regulu bithuungan'": Neue Arbeiten zur althochdeutschen Poesie und Sprache. Göppingen: Kümmerle. pp. 80–93. ISBN 3-87452-737-9.

- Fought, John (1979). "The 'Medieval Sibilants' of the Eulalia–Ludwigslied Manuscript and Their Development in Early Old French". Language. 55 (4): 842–58. doi:10.2307/412747. JSTOR 412747.

- Freytag W (1985). "Ludwigslied". In Ruh K, Keil G, Schröder W (eds.). Die deutsche Literatur des Mittelalters. Verfasserlexikon. Vol. 5. Berlin, New York: Walter De Gruyter. cols. 1036–1039. ISBN 978-3-11-022248-7.

- Green, Dennis H. (2002). "The "Ludwigslied" and the Battle of Saucourt". In Jesch, Judith (ed.). The Scandinavians from the Vendel period to the tenth century. Cambridge: Boydell. pp. 281–302. ISBN 9780851158679.

- Grimm, Jacob (1856). "Über das Ludwigslied". Germania. 1: 233–235. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- Groseclose, J Sidney; Murdoch, Brian O (1976). "Ludwigslied". Die althochdeutschen poetischen Denkmäler. Stuttgart: Metzler. pp. 67–77. ISBN 3-476-10140-1.

- Handschriftencensus (2024). "Handschriftenbeschreibung 7591". Handschriftencensus. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- Harvey, Ruth (1945). "The Provenance of the Old High German Ludwigslied". Medium Aevum. 14: 1–20. doi:10.2307/43626303. JSTOR 43626303.

- Haubrichs, Wolfgang (1995). "Das Schlacht- und Fürstenpreislied". Die Anfänge: Versuche volkssprachlicher Schriftlichkeit im frühen Mittelalter (ca. 700-1050/60). Geschichte der deutschen Literatur von den Anfängen bis zum Beginn der Neuzeit. Vol. 1/1 (2nd ed.). Tübingen: Niemeyer. pp. 137–146. ISBN 978-3484107014.

- ———— (2023). "Rustica Romana lingua und Theotisca lingua – Frühmittelalterliche Mehrsprachigkeit im Raum von Rhein, Maas und Mosel". In Franceschini, Rita; Hüning, Matthias; Maitz, Péter (eds.). Historische Mehrsprachigkeit: Europäische Perspektiven. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. pp. 179–206. doi:10.1515/9783111338668-009. ISBN 9783111338668.

- Hellgardt, Ernst (1996). "Zur Mehrsprachigkeit im Karolingerreich: Bemerkungen aus Anlaß von Rosamond McKittericks Buch "The Carolingians and the written word"". Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und Literatur. 118: 1–48. doi:10.1515/bgsl.1996.1996.118.1.

- Herweg, Matthias (2013). "Ludwigslied". In Bergmann, Rolf (ed.). Althochdeutsche und altsächsische Literatur. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. pp. 241–252. ISBN 978-3-11-024549-3.

- Horváth, Iván (2014). "When Literature Itself Was Bilingual: A Rule of Vernacular Insertions" (PDF). Ars Metrica (11).

- Marold, Edith (2001). "Preislied". In Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Vol. 23. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 398–408. ISBN 3-11-017163-5. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- Maurer, Friedrich (1957). "Hildebrandslied und Ludwigslied. Die altdeutschen Zeugen der hohen Gattungen der Wanderzeit". Der Deutschunterricht. 9: 5–15. Reprinted in: Maurer, Friedrich (1963). Dichtung und Sprache des Mittelalters, Gesammelte Aufsätze. Bern: Francke. pp. 157–163. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- McKitterick, Rosamond (2008). The Carolingians and the Written Word. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 232–235. ISBN 978-0521315654.

- Metzner, Ernst E (2001). "Ludwigslied". In Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Vol. 19. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 12–17. ISBN 3-11-017163-5. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- Murdoch, Brian (1977). "Saucourt and the Ludwigslied: Some Observations on Medieval Historical Poetry". Revue belge de Philologie et d'Histoire. 55 (3): 841–67. doi:10.3406/rbph.1977.3161.

- ———— (2004). "Heroic Verse". In Murdoch, Brian (ed.). German Literature of the Early Middle Ages. Camden House History of German Literature. Vol. 2. Rochester, NY; Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. pp. 121–138. ISBN 1-57113-240-6.

- Platelle, Henri (1961). "Les effets des raids scandinaves à Saint-Amand (881, 883)". Revue du Nord. 43 (169): 129. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- Rossi, Albert Louis (1986). Vernacular Authority in the Late Ninth Century: Bilingual Juxtaposition in MS 150, Valenciennes (Eulalia, Ludwigslied, Gallo-Romance, Old High German) (PhD thesis). Princeton University.

- Schneider, Jens (2003). "Les Northmanni en Francie occidentale au IXe siècle. Le chant de Louis". Annales de Normandie. 53 (4): 291–315. doi:10.3406/annor.2003.1453. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- Schützeichel, Rudolf (1966–1967). "Das Ludwigslied und die Erforschung des Westfränkischen". Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter. 31: 291–306. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- Schwarz, Werner (1947). "The "Ludwigslied", a Ninth-Century Poem". Modern Language Review. 42 (2): 467–473. doi:10.2307/3716800. JSTOR 3716800.

- Wolf, Alois. "Medieval Heroic Traditions and Their Transitions from Orality to Literacy". In Vox Intexta: Orality and Textuality in the Middle Ages, ed. A. N. Doane and C. B. Pasternack, 67–88. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1991. Limited preview at Google Books

- Yeandle, David N (1989). "The Ludwigslied: King, Church and Context". In Flood, John L; Yeandle, David N (eds.). "'Mit regulu bithuungan'": Neue Arbeiten zur althochdeutschen Poesie und Sprache. Göppingen: Kümmerle. pp. 18–79. ISBN 3-87452-737-9.

- Young, Christopher; Gloning, Thomas (2004). A History of the German Language through texts. London, New York: Routledge. pp. 77–85. ISBN 0-415-18331-6.

External links

- Le Rithmus teutonicus ou Ludwigslied - facsimile and bibliography from the Bibliothèque Municipale, Valenciennes (in French)

- High quality facsimile of all four sheets (Bibliotheca Augustana)

- Facsimile of whole manuscript (Portail Biblissima)

- Transcription of the text (Bibliotheca Augustana)

- OHG text from Wright's Old High German Primer (1888)

- OHG text and modern German translation

- OHG text with modern French translation