Informatics Educational Institutions & Programs

Contents

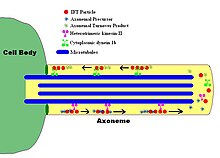

Intraflagellar transport (IFT) is a bidirectional motility along axoneme microtubules that is essential for the formation (ciliogenesis) and maintenance of most eukaryotic cilia and flagella.[1] It is thought to be required to build all cilia that assemble within a membrane projection from the cell surface. Plasmodium falciparum cilia and the sperm flagella of Drosophila are examples of cilia that assemble in the cytoplasm and do not require IFT. The process of IFT involves movement of large protein complexes called IFT particles or trains from the cell body to the ciliary tip and followed by their return to the cell body. The outward or anterograde movement is powered by kinesin-2 while the inward or retrograde movement is powered by cytoplasmic dynein 2/1b. The IFT particles are composed of about 20 proteins organized in two subcomplexes called complex A and B.[2]

IFT was first reported in 1993 by graduate student Keith Kozminski while working in the lab of Dr. Joel Rosenbaum at Yale University.[3][4] The process of IFT has been best characterized in the biflagellate alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii as well as the sensory cilia of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans.[5]

It has been suggested based on localization studies that IFT proteins also function outside of cilia.[6]

Biochemistry

Intraflagellar transport (IFT) describes the bi-directional movement of non-membrane-bound particles along the doublet microtubules of the flagellar, and motile cilia axoneme, between the axoneme and the plasma membrane. Studies have shown that the movement of IFT particles along the microtubule is carried out by two different microtubule motors; the anterograde (towards the flagellar tip) motor is heterotrimeric kinesin-2, and the retrograde (towards the cell body) motor is cytoplasmic dynein 1b. IFT particles carry axonemal subunits to the site of assembly at the tip of the axoneme; thus, IFT is necessary for axonemal growth. Therefore, since the axoneme needs a continually fresh supply of proteins, an axoneme with defective IFT machinery will slowly shrink in the absence of replacement protein subunits. In healthy flagella, IFT particles reverse direction at the tip of the axoneme, and are thought to carry used proteins, or "turnover products," back to the base of the flagellum.[7][8]

The IFT particles themselves consist of two sub-complexes,[9] each made up of several individual IFT proteins. The two complexes, known as 'A' and 'B,' are separable via sucrose centrifugation (both complexes at approximately 16S, but under increased ionic strength complex B sediments more slowly, thus segregating the two complexes). The many subunits of the IFT complexes have been named according to their molecular weights:

- complex A contains IFT144, IFT140, IFT139, IFT122,[2] IFT121 and IFT43[10]

- complex B contains IFT172, IFT88, IFT81, IFT80, IFT74, IFT72, IFT57, IFT52, IFT46, IFT27, and IFT20[2]

The biochemical properties and biological functions of these IFT subunits are just beginning to be elucidated, for example they interact with components of the basal body like CEP170 or proteins which are required for cilium formation like tubulin chaperone and membrane proteins.[11]

Physiological importance

Due to the importance of IFT in maintaining functional cilia, defective IFT machinery has now been implicated in many disease phenotypes generally associated with non-functional (or absent) cilia. IFT88, for example, encodes a protein also known as Tg737 or Polaris in mouse and human, and the loss of this protein has been found to cause an autosomal-recessive polycystic kidney disease model phenotype in mice. Further, the mislocalization of this protein following WDR62 knockdown in mice results in brain malformation and ciliopathies.[12] Other human diseases such as retinal degeneration, situs inversus (a reversal of the body's left-right axis), Senior–Løken syndrome, liver disease, primary ciliary dyskinesia, nephronophthisis, Alström syndrome, Meckel–Gruber syndrome, Sensenbrenner syndrome, Jeune syndrome, and Bardet–Biedl syndrome, which causes both cystic kidneys and retinal degeneration, have been linked to the IFT machinery. This diverse group of genetic syndromes and genetic diseases are now understood to arise due to malfunctioning cilia, and the term "ciliopathy" is now used to indicate their common origin.[13] These and possibly many more disorders may be better understood via study of IFT.[7]

| IFT gene | Other name | Human disease | reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| IFT27 | RABL4 | Bardet–Biedl syndrome | [14] |

| IFT43 | C14ORF179 | Sensenbrenner syndrome | [15] |

| IFT121 | WDR35 | Sensenbrenner syndrome | [16] |

| IFT122 | WDR10 | Sensenbrenner syndrome | [17] |

| IFT140 | KIAA0590 | Mainzer–Saldino syndrome | [18] |

| IFT144 | WDR19 | Jeune syndrome, Sensenbrenner syndrome | [19] |

| IFT172 | SLB | Jeune syndrome, Mainzer–Saldino syndrome | [20] |

One of the most recent discoveries regarding IFT is its potential role in signal transduction. IFT has been shown to be necessary for the movement of other signaling proteins within the cilia, and therefore may play a role in many different signaling pathways. Specifically, IFT has been implicated as a mediator of sonic hedgehog signaling,[21] one of the most important pathways in embryogenesis.

References

- ^ "The Panda's Thumb: Of cilia and silliness (More on Behe)". www.pandasthumb.org. Archived from the original on 14 September 2007. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Cole, DG; Diener, DR; Himelblau, AL; Beech, PL; Fuster, JC; Rosenbaum, JL (May 1998). "Chlamydomonas kinesin-II-dependent intraflagellar transport (IFT): IFT particles contain proteins required for ciliary assembly in Caenorhabditis elegans sensory neurons". J. Cell Biol. 141 (4): 993–1008. doi:10.1083/jcb.141.4.993. PMC 2132775. PMID 9585417.

- ^ Bhogaraju, S.; Taschner, M.; Morawetz, M.; Basquin, C.; Lorentzen, E. (2011). "Crystal structure of the intraflagellar transport complex 25/27". The EMBO Journal. 30 (10): 1907–1918. doi:10.1038/emboj.2011.110. PMC 3098482. PMID 21505417.

- ^ Kozminski, KG; Johnson KA; Forscher P; Rosenbaum JL. (1993). "A motility in the eukaryotic flagellum unrelated to flagellar beating". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 90 (12): 5519–23. Bibcode:1993PNAS...90.5519K. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.12.5519. PMC 46752. PMID 8516294.

- ^ Orozco, JT; Wedaman KP; Signor D; Brown H; Rose L; Scholey JM (1999). "Movement of motor and cargo along cilia". Nature. 398 (6729): 674. Bibcode:1999Natur.398..674O. doi:10.1038/19448. PMID 10227290. S2CID 4414550.

- ^ Sedmak T, Wolfrum U (April 2010). "Intraflagellar transport molecules in ciliary and nonciliary cells of the retina". J. Cell Biol. 189 (1): 171–86. doi:10.1083/jcb.200911095. PMC 2854383. PMID 20368623.

- ^ a b Rosenbaum, JL; Witman GB (2002). "Intraflagellar Transport". Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 3 (11): 813–25. doi:10.1038/nrm952. PMID 12415299. S2CID 12130216.

- ^ Scholey, JM (2008). "Intraflagellar transport motors in cilia: moving along the cell's antenna". Journal of Cell Biology. 180 (1): 23–29. doi:10.1083/jcb.200709133. PMC 2213603. PMID 18180368.

- ^ Lucker BF, Behal RH, Qin H, et al. (July 2005). "Characterization of the intraflagellar transport complex B core: direct interaction of the IFT81 and IFT74/72 subunits". J. Biol. Chem. 280 (30): 27688–96. doi:10.1074/jbc.M505062200. PMID 15955805.

- ^ Behal RH1, Miller MS, Qin H, Lucker BF, Jones A, Cole DG. (2012). "Subunit interactions and organization of the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii intraflagellar transport complex A proteins". J. Biol. Chem. 287 (15): 11689–703. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.287102. PMC 3320918. PMID 22170070.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Lamla S (2009). Functional characterisation of the centrosomal protein Cep170. Dissertation (Text.PhDThesis). LMU Muenchen: Fakultät für Biologie.

- ^ Shohayeb, B, et al. (December 2020). "The association of microcephaly protein WDR62 with CPAP/IFT88 is required for cilia formation and neocortical development". Hum. Mol. Genet. 29 (2): 248–263. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddz281. PMID 31816041.

- ^ Badano, Jose L.; Norimasa Mitsuma; Phil L. Beales; Nicholas Katsanis (September 2006). "The Ciliopathies : An Emerging Class of Human Genetic Disorders". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 7: 125–148. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115610. PMID 16722803.

- ^ Aldahmesh, M. A., Li, Y., Alhashem, A., Anazi, S., Alkuraya, H., Hashem, M., Awaji, A. A., Sogaty, S., Alkharashi, A., Alzahrani, S., Al Hazzaa, S. A., Xiong, Y., Kong, S., Sun, Z., Alkuraya, F. S. (2014). "IFT27, encoding a small GTPase component of IFT particles, is mutated in a consanguineous family with Bardet-Biedl syndrome". Hum. Mol. Genet. 23 (12): 3307–3315. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddu044. PMC 4047285. PMID 24488770.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Arts, H. H., Bongers, E. M. H. F., Mans, D. A., van Beersum, S. E. C., Oud, M. M., Bolat, E., Spruijt, L., Cornelissen, E. A. M., Schuurs-Hoeijmakers, J. H. M., de Leeuw, N., Cormier-Daire, V., Brunner, H. G., Knoers, N. V. A. M., Roepman, R. (2011). "C14ORF179 encoding IFT43 is mutated in Sensenbrenner syndrome". J. Med. Genet. 48 (6): 390–395. doi:10.1136/jmg.2011.088864. PMID 21378380. S2CID 6073572.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gilissen, C., Arts, H. H., Hoischen, A., Spruijt, L., Mans, D. A., Arts, P., van Lier, B., Steehouwer, M., van Reeuwijk, J., Kant, S. G., Roepman, R., Knoers, N. V. A. M., Veltman, J. A., Brunner, H. G. (2010). "Exome sequencing identifies WDR35 variants involved in Sensenbrenner syndrome". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 87 (3): 418–423. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.08.004. PMC 2933349. PMID 20817137.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Walczak-Sztulpa, J., Eggenschwiler, J., Osborn, D., Brown, D. A., Emma, F., Klingenberg, C., Hennekam, R. C., Torre, G., Garshasbi, M., Tzschach, A., Szczepanska, M., Krawczynski, M., Zachwieja, J., Zwolinska, D., Beales, P. L., Ropers, H.-H., Latos-Bielenska, A., Kuss, A. W. (2010). "Cranioectodermal dysplasia, Sensenbrenner syndrome, is a ciliopathy caused by mutations in the IFT122 gene". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 86 (6): 949–956. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.012. PMC 3032067. PMID 20493458.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Perrault, I., Saunier, S., Hanein, S., Filhol, E., Bizet, A. A., Collins, F., Salih, M. A. M., Gerber, S., Delphin, N., Bigot, K., Orssaud, C., Silva, E., and 18 others. (2012). "Mainzer-Saldino syndrome is a ciliopathy caused by IFT140 mutations". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90 (5): 864–870. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.03.006. PMC 3376548. PMID 22503633.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Bredrup, C., Saunier, S., Oud, M. M., Fiskerstrand, T., Hoischen, A., Brackman, D., Leh, S. M., Midtbo, M., Filhol, E., Bole-Feysot, C., Nitschke, P., Gilissen, C., and 16 others. (2011). "Ciliopathies with skeletal anomalies and renal insufficiency due to mutations in the IFT-A gene WDR19". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 89 (5): 634–643. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.10.001. PMC 3213394. PMID 22019273.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Halbritter, J., Bizet, A. A., Schmidts, M., Porath, J. D., Braun, D. A., Gee, H. Y., McInerney-Leo, A. M., Krug, P., Filhol, E., Davis, E. E., Airik, R., Czarnecki, P. G., and 38 others. (2013). "Defects in the IFT-B component IFT172 cause Jeune and Mainzer-Saldino syndromes in humans". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 93 (5): 915–925. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.09.012. PMC 3824130. PMID 24140113.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Eggenschwiler JT, Anderson KV (January 2007). "Cilia and developmental signaling". Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 23: 345–73. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123249. PMC 2094042. PMID 17506691.

Further reading

- Orozco JT, Wedaman KP, Signor D, Brown H, Rose L, Scholey JM (April 1999). "Movement of motor and cargo along cilia". Nature. 398 (6729): 674. Bibcode:1999Natur.398..674O. doi:10.1038/19448. PMID 10227290. S2CID 4414550.

- Cole DG, Diener DR, Himelblau AL, Beech PL, Fuster JC, Rosenbaum JL (May 1998). "Chlamydomonas kinesin-II-dependent intraflagellar transport (IFT): IFT particles contain proteins required for ciliary assembly in Caenorhabditis elegans sensory neurons". J. Cell Biol. 141 (4): 993–1008. doi:10.1083/jcb.141.4.993. PMC 2132775. PMID 9585417.

- Pan X, Ou G, Civelekoglu-Scholey G, et al. (September 2006). "Mechanism of transport of IFT particles in C. elegans cilia by the concerted action of kinesin-II and OSM-3 motors". J. Cell Biol. 174 (7): 1035–45. doi:10.1083/jcb.200606003. PMC 2064394. PMID 17000880.

- Qin H, Burnette DT, Bae YK, Forscher P, Barr MM, Rosenbaum JL (September 2005). "Intraflagellar transport is required for the vectorial movement of TRPV channels in the ciliary membrane". Curr. Biol. 15 (18): 1695–9. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.047. PMID 16169494. S2CID 15658145.

- Haycraft CJ, Banizs B, Aydin-Son Y, Zhang Q, Michaud EJ, Yoder BK (October 2005). "Gli2 and Gli3 localize to cilia and require the intraflagellar transport protein polaris for processing and function". PLOS Genet. 1 (4): e53. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0010053. PMC 1270009. PMID 16254602.

- Briggs LJ, Davidge JA, Wickstead B, Ginger ML, Gull K (August 2004). "More than one way to build a flagellum: comparative genomics of parasitic protozoa". Curr. Biol. 14 (15): R611–2. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.041. PMID 15296774. S2CID 42754598.

External links

- For a time-lapse microscopic QuickTime movie and schematic cartoon of IFT, see Rosenbaum Lab IFT webpage.