Informatics Educational Institutions & Programs

Contents

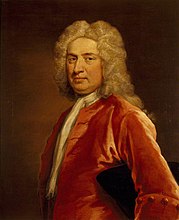

John Vanderbank | |

|---|---|

Self Portrait (c. 1720) | |

| Born | 9 September 1694 |

| Died | 23 December 1739 (aged 45) London, Great Britain |

| Nationality | English |

| Education | Jonathan Richardson, Sir Godfrey Kneller, |

| Known for | A leading portrait painter of England |

John Vanderbank (9 September 1694 – 23 December 1739) was an English painter who enjoyed a high reputation during the last decade of King George I's reign and remained in high fashion in the first decade of King George II's reign.[1] George Vertue's opinion was that only intemperance and extravagance prevented Vanderbank from being the greatest portraitist of his generation, his lifestyle bringing him into repeated financial difficulties and leading to an early death at the age of only 45.[2]

Early life

Vanderbank was born in London on 9 September 1694 into an artistic family, the eldest son of Sarah and John Vanderbank Snr, a naturalised Huguenot immigrant from Paris and, since 1679, well-to-do proprietor of the Soho Tapestry Manufactory and Yeoman Arras-maker to the Great Wardrobe, supplying the royal family with tapestries from his premises in Great Queen Street, Covent Garden.[3] John Vanderbank senior was the leading tapestry weaver in England throughout his life and by the introduction of the lighter and less formal style, now referred to as chinoiserie, he exercised a powerful influence on the style of the Soho weavers.[4]

John Vanderbank first studied composition and painting under his father and then the painter Jonathan Richardson, before becoming one of Sir Godfrey Kneller's earliest pupils in 1711 at his art academy in Great Queen Street, neighbouring his father's tapestry workshop. After Sir James Thornhill took over from Kneller in 1718, Vanderbank continued his studies there for two years before founding an academy of his own in 1720.

Vanderbank's younger brother, Moses Vanderbank, was also an artist and draughtsman, although besides a family group depicting three children (1733), three altarpieces in the 12th century church at Adel near Leeds,[5] and a portrait of a young child with a lamb (1743), his painted works are exceptionally rare.[6] He succeeded his father to the post of Yeoman Arras-maker to the Crown in 1727.[7]

The family's relationship to the leading late 17th century painter and engraver Peter Vanderbank is uncertain although the Parisian origins of both, the similarity of profession, the facial similarities of Kneller's chalk portrait of Peter Vanderbank and John Vanderbank's self-portrait drawing, and John Vanderbank senior's ownership of land in Hertfordshire where Peter Vanderbank married and spent his final years are suggestive.[8]

Career

Portrait painter

Vanderbank worked chiefly as a portraitist, also painting some allegorical subjects, and as an illustrator. He began his portrait practice in 1719 with a large equestrian portrait of Charles Spencer, 3rd Duke of Marlborough, developing a free, painterly style, his faces admirably drawn with what Vertue describes as ‘greatness of pencilling, spirit and composition’,[1] and partly derived from his admiration for Rubens and Van Dyck, many of whose works he had studiously copied. His early portraits continued the vigour and grand style of Kneller but with a more vital and energetic drawing than his contemporaries. He used a bold pigmentation in the flesh where pink tones are painted thinly over the cooler greys of the ground layer to suggest glowing skin, the technique of colori cangianti derived from Rubens who was himself inspired by the artists of the seicento. Equally distinctive is the way in which mid-tones are represented by unpainted areas of grey-green primer and the placing of pure red pigments for highlights.[9]

Vanderbank's academy

In 1720, after a period of infighting, Thornhill closed Kneller's Academy and opened a new academy of his own, conducting free life-drawing classes from a room he added to his own house in James Street, Covent Garden.[10] In October of the same year a faction led by John Vanderbank, who on his father's death in 1717 had received a legacy of £500,[11] and the elderly Louis Chéron established an academy which they advertised as 'The Academy for the Improvement of Painters and Sculptors by drawing from the Naked' at premises in St Martin's Lane. Vanderbank's Academy, as it became known, proved popular and its list of subscribers is a roll call of the next generation of leading artists. Conversely Thornhill had little success in finding subscribers, despite making no charge, and Hogarth, Thornhill's son-in-law, attributed its failure at least in part to the competition from Vanderbank's Academy. In 1724 it was discovered that the academy treasurer had embezzled the subscription funds[12] and this, coupled with Vanderbank's growing debt problems, and perhaps Chéron's old age and illness (he died in May of the following year), led to the closure of the academy that summer.

Vanderbank's Academy was shortlived but had an important influence on the development of English art, not least by furthering the introduction in England of life drawing classes for promising students such as William Hogarth, Joseph Highmore, William Kent, John Faber, John Ellys and James Seymour.[13] Moreover in leading the academy Vanderbank was at the centre of an influential artistic hub enjoying the patronage of the wealthiest aristocrats, largely responsible for shaping the taste and cultural life of England in the 1720s and 1730s, encompassing art, architecture, music and the landscape. For example when William Kent joined Vanderbank's Academy he was already painting interiors at Cannons for the Duke of Chandos,[14] the princely palace designed by James Gibbs whom Vanderbank had known since Kneller's Academy, and in 1722 Vanderbank painted a portrait of the Duke of Chandos which has in the background the great basin lake created at Cannons (of which Nicholas Hawksmoor said "I cannot but own that the water at Cannon's... is the main beauty of that situation and it cost him dear",[15] and in 1727 Hogarth, probably on Vanderbank's recommendation, was invited to paint a cartoon of The Element of the Earth for Joshua Morris, the tapestry maker of Great Queen Street, for some hangings for Cannons, so initiating Hogarth's painting career.[16] The Duke of Chandos had installed Handel as musician in residence at Cannons,[17] where he composed the Chandos Anthems and his first oratorios, and in 1719 was one of the principal founding subscribers to the Royal Academy of Music to ensure a steady supply of baroque opera under Handel's aegis. Vanderbank was a frequent concert goer, drawing a caricature of Senesino, Cuzzoni and Berenstadt in a scene from Handel's Flavio in 1723,[18] which was anonymously etched and engraved, and in the same year painting the portrait of the leading soprano, and later contralto, Anastasia Robinson, Countess of Peterborough, of which Faber produced a popular mezzotint in 1727.

Vanderbank's extravagant habits saw him repeatedly in financial difficulties between 1724 and 1729, when his debts were cleared by his brother Moses. From 1729 John Vanderbank occupied a house in Holles Street, Cavendish Square, rent-free thanks to the generous patronage of Lord Carteret who, however, appropriated the contents of his studio after his death. According to Vertue, there Vanderbank lived ‘galantly or freely according to the custom of the Age’[19] and so in the 1730s Vanderbank's career returned to the ascendant, Vertue noting that he had 'a great run of business painting persons of quality and distinction'.

Works

Vanderbank's portraits of royalty, leading aristocrats and eminent persons of his day are to be found in every major art gallery around the world including the Metropolitan Museum of Art,[20] National Gallery of Art, Washington DC,[21] Royal Academy of Arts,[22] Tate Gallery,[23] The Royal Collection,[24] The Courtauld Gallery,[25] the Dulwich Picture Gallery,[26] and the National Portrait Gallery.[27] A great many of Vanderbank's portraits were engraved in mezzotint by John Faber, George Vertue, George White and others, and were highly popular at the time.

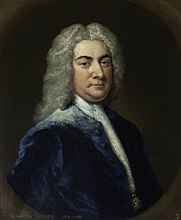

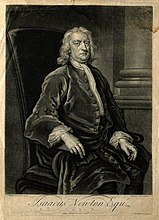

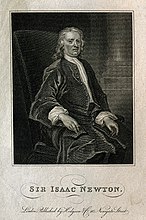

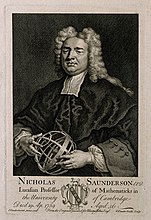

Vanderbank's most characterful and distinguished portraits are generally of the 1720s including the great patron of Handel and of the arts the Duke of Chandos (1722), the two portraits of Sir Isaac Newton (1725 and 1726), the painter George Lambert (untraced but engraved by Faber in 1727), the eccentric Newmarket trainer Tregonwell Frampton (c.1725), the poet James Thomson (1726), and the sculptor John Michael Rysbrack (c.1728). Ellis Waterhouse considered that Vanderbank's masterpiece was the large full-length of Queen Caroline (1736). Vanderbank painted three allegorical subjects incorporating an equestrian portrait of George I for the decoration of the staircase at 11 Bedford Row, London, and contributed The Apotheosis, or, Death of the King (1727) to the series of ten paintings by various artists, including Chéron and Pieter Angelis, engraved in 1728 and advertised by John Bowles as Ten Prints of the Reign of King Charles the First. By contrast, some of Vanderbank's later portraits of ‘persons of Quality’, male or female, are technically well painted but can betray a lack of rapport with his sitters and a tendency to rely on stock poses sometimes directly derived from Van Dyck. Vertue noted that, like many portraitists of the period, Vanderbank sometimes used the services of the drapery painter Joseph Van Aken from the mid 1730s.[28][29]

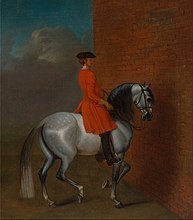

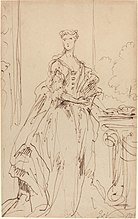

As a draughtsman and illustrator, Vanderbank demonstrates a verve and originality not always found in his portraiture.[30] A series of pen, ink, and wash drawings of horses and riders being trained in the exercises of haute école, drawn in the early 1720s when the artist ‘was himself a Disciple in our Riding-Schools’[31] was engraved and published by Joseph Sympson in 1729 as 'Twenty Five Actions of the Manage Horse'. The drawings were widely copied and pirated. In 1723 Vanderbank was commissioned by the publishers J and R Tonson to illustrate Don Quixote, in the original Spanish and this eventually appeared as a lavish four-volume quarto edition in 1738 with sixty-eight engraved plates after Vanderbank.[32] This project, for which Vanderbank's initial designs were preferred over Hogarth's, appears to have preoccupied Vanderbank, perhaps almost empathetically, for the remainder of his life, resulting in three sets of drawings; first sketched then finished for the engraver's use, then drawn afresh, elaborated, and fully finished, as well as a series of some thirty-five small freely painted oil panels. Vanderbank also illustrated or designed frontispieces for various volumes of plays.[33]

Vanderbank's only known apprentice was John Robinson (1715-1745) whom he took on for five years for a premium of £157 10s on 23 July 1737. Robinson attained some success as a portrait-painter in his short life. Having married a wife with a fortune, he purchased the late Charles Jervas's house in Cleveland Court, Bath, and thus inherited a fashionable practice.[34][2]

Character

From Vertue we know that Vanderbank was immensely talented, 'so bold and free was his pencil and so masterly his drawing', and also that Vanderbank might have made a greater figure than almost any painter England had produced had he not been so careless and extravagant; 'only intemperance prevented Vanderbank from being the greatest portraitist of his generation'.[35]

Vertue notes that Vanderbank ‘livd very extravagantly a mistres drinking & country house a purpose for her’.[36] This extravagance led him into debt and in 1724 Vanderbank fled to France briefly to avoid imprisonment by his creditors,[37] returning to enter 'the liberties of the Fleet', mansion houses near the Fleet prison in which privileged prisoners could enjoy relative comfort in return for payment.[2] In 1727 Vanderbank's mother died, having prudently left her assets out of reach of John's creditors to her younger son Moses, and in 1729 Moses sold a share in the family tapestry business to the painter John Ellys to settle John Vanderbank's debts. Vanderbank then accepted a free residence in Lord Carteret's house in Holles Street, neighbouring the Duke of Chandos's house in Cavendish Square, London.[8]

That Vanderbank succeeded in remaining in the first rank of portraitists in the 1720s and again in the 1730s in spite of his intemperance, sometimes producing outstanding works of art, testifies to the accuracy of Vertue's opinion.[38]

Personal life

On 12 July 1723 Vanderbank married the actress Ann Hardaker (b 1703) at St Mary's Church, Islington,[39] the daughter of William Hardaker and Sibella (née Mountjoy)[40] of Holborn, London. She was deemed by Vertue to be ‘a Vain empty wooman’ though, judging by the portrait miniature by Christian Friedrich Zincke and Faber's mezzotint from her portrait by her husband, she was certainly strikingly attractive.[41] The Hardakers had links to the West Riding of Yorkshire where Vanderbank's older sister Elizabeth had married John Hotham in 1715. This northern connection might have been the source of Moses Vanderbank's commission in Leeds. Vertue noted that Vanderbank ‘left no children behind him by this wooman’ and indeed none has ever been traced from the marriage.

Vanderbank died of consumption (tuberculosis) in Holles Street on 23 December 1739 aged 45 and was buried in St Marylebone Parish Church, Westminster.[2] In his will, dated 19 December 1739 and made four days before he died, he leaves his entire estate "unto my dear wife".[42] Anne Vanderbank died in 1750 and was buried at St George Hanover Square[43]

Other paintings

Drawings

Engravings and mezzotints

References

- ^ a b Waterhouse, Ellis. Painting in Britain 1530–1790 (Penguin Books, 1957).

- ^ a b c d Lee, Sidney, ed. (1899). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 58. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 100.

- ^ Amal Asfour, Paul Williamson. Gainsborough's vision (Liverpool University Press, 1999) p71.

- ^ Survey of London: Volumes 33 and 34, St Anne Soho. Originally published by London County Council, London, 1966, Appendix 1: The Soho Tapestry Makers, pages 515-520

- ^ John Mayhall, The Annals and History of Leeds and Other Places in the County York, Kirkstall,1860, p27. p138

- ^ "Moses vanderbank"..

- ^ Egerton, Judy (2004). "Vanderbank, John (1694–1739), painter and draughtsman". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28067. Retrieved 31 August 2020. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b Survey of London: Volumes 33 and 34, St Anne Soho, London County Council, London, 1966, Appendix 1: The Soho Tapestry Makers, pages 515-520

- ^ "John Vanderbank, Philip Mould, Historical Portraits"..

- ^ William Sandby, The History of the Royal Academy of Arts from Its Foundation in 1768 (London: Longmans, Green) 1862:21.

- ^ The Will of Johannis Vanderbank, proved 1717, The National Archives; Kew, Surrey, England; Records of the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, Series PROB 11; Class: PROB 11; Piece: 559

- ^ James Ayres, Art, Artisans and Apprentices: Apprentice Painters & Sculptors in the Early Modern British Tradition, 2014.

- ^ "John Vanderbank, Philip Mould, Historical Portraits".

- ^ Tim Mowl, William Kent: Architect, Designer, Opportunist, 2006, p101

- ^ Jenkins, Susan (2007). Portrait of a Patron. The Patronage and Collecting of James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos (1674–1744). Ashgate Publishing. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-7546-4156-8.

- ^ Ronald Paulson, Hogarth, The modern Moral Subject, 1697-1732, 1991, p155.

- ^ Paul Henry Lang, George Frideric Handel, 1966, p258.

- ^ "John vanderbank, Berenstadt, Cuzzoni and Senesino by John Vanderbank, The British Museum".

- ^ Vertue, Note books, 3.97

- ^ "John Vanderbank, the Metropolitan Museum of Art".

- ^ "John Vanderbank, National Gallery of Art, Washington".

- ^ "John Vanderbank, Royal Academy of Arts".

- ^ "John Vanderbank, Tate Gallery".

- ^ "John Vanderbank, The Royal Collection".

- ^ "John Vanderbank, The Courtauld Gallery".

- ^ "John Vanderbank, Dulwich Picture Gallery".

- ^ "John Vanderbank, National Portrait Gallery".

- ^ Manners and Morals, p.247

- ^ Egerton, Judy (2004). "Vanderbank, John (1694–1739), painter and draughtsman". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28067. Retrieved 31 August 2020. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Hammelmann, H.A. (1968). "John Vanderbank 1694-1737." The Book Collector 17 no 3 (autumn): 285-299.

- ^ Alejandra Aguado, Martin Myrone, Tate Britain: 100 Works from the Tate Collection, 2007, p7

- ^ Hammelmann, H. A. “John Vanderbank’s ‘Don Quixote.’” Master Drawings 7, no. 1 (1969): 3–74.

- ^ Egerton, Judy (2004). "Vanderbank, John (1694–1739), painter and draughtsman". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28067. Retrieved 31 August 2020. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Henry B Wheatley FSA, Historical Portraits, London, 1897, p66

- ^ George Vertue, Note books 5.98

- ^ "Friends of Marble Hill, Research Articles".

- ^ George Vertue, Note books 3.98

- ^ Horace Walpole, Anecdotes of Painting in England, 1849, vol 2, p676

- ^ Original data: England, Marriages, 1538–1973. Salt Lake City, Utah: FamilySearch, 2013.

- ^ Marriage register, 10 May 1702 at St Mary, Whitechapel, Middlesex, England, London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Reference Number: P93/MRY1/006

- ^ Church of England Parish Registers, 1538-1812. London, England: London Metropolitan Archives, Reference Number: P83/MRY1/1167

- ^ The National Archives' reference PROB 11/703/152

- ^ City of Westminster Archives Centre; London, England; Westminster Church of England Parish Registers; Reference: STC/PR/5/22.

External links

- 102 artworks by or after John Vanderbank at the Art UK site

- J. Vanderbank online (ArtCyclopedia)

- J. Vanderbank biography (Philip Mould Fine Paintings)

- Historical portraits by John Vanderbank (Philip Mould Fine Paintings)

- Portrait of Miss Rachel Long (1737, oil on canvas)

- Portrait of a gentleman (Art Renewal center)