Informatics Educational Institutions & Programs

Contents

Radioactive quackery is quackery that improperly promotes radioactivity as a therapy for illnesses. Unlike radiotherapy, which is the scientifically sound use of radiation for the destruction of cells (usually cancer cells), quackery pseudo-scientifically promotes involving radioactive substances as a method of healing for cells and tissues. It was most popular during the early 20th century, after the discovery in 1896 of radioactive decay.[1] The practice has widely declined, but is still actively practiced by some.[2]

Notable examples

- Tho-Radia, a cream containing radium bromide, notable for its iconic advertising and for employing a homonyme of Pierre and Marie Curie with no connection to them as a marketing device.

- Radithor, a solution of radium salts, which was claimed by its developer William J. A. Bailey to have curative properties. Industrialist Eben Byers died in 1932 from ingesting it in large quantities throughout 1927–1930.[3][4]

- One German brand of toothpaste from prior to the Second World War, Doramad Radioactive Toothpaste, contained small amounts of thorium that was a byproduct in the manufacture of gas lamp mantles. The advertising for this toothpaste stated "Your teeth will shine with radioactive brilliance".[5]

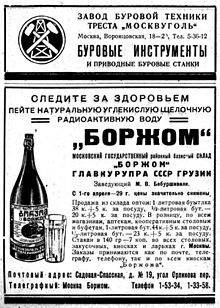

- A number of spas that treat visitors with naturally infused radon water from the local hills were founded in 1906 and onwards in Jáchymov, Czech Republic, and still exist today.[6] These spas were world-renowned, as evidenced by an article in the New Zealand Thames Star Supplement from 1912 (the article uses the Austrian name of the town, Joachimsthal).[7] Similar spas currently exist in Germany, Ukraine and Austria[8][9] and in Germany they are covered by public health insurance.[10]

- Revigator pots, which added radon to drinking water.[1]

- Uranium sand houses, where patients would sit on benches in a round room that had a floor composed of mildly radioactive sand (usually beach sand with crushed minerals like carnotite). These were popular in Utah, New Mexico, and Colorado during the 1950s.[11]

- Lying in a narrow box with sands that reputedly contained uranium ore was promoted as a treatment for arthritis, bursitis, and rheumatism as late as 1956.[12]

- The NICO Clean Tobacco Card was a device exported from Japan to the United States in the 1960s, consisting of a small card with low-grade uranium ore on one side.[13] The card was to be placed inside a pack of cigarettes, and the producers claimed that the radiation emitted by the card would reduce tar and nicotine. A similar product called the Nicotine Alkaloid Control Plate is reported to have contained monazite sand (with thorium).[14]

- Various consumer products such as jewelry, pendants, wristbands and athletic tape are touted as incorporating "negative ion technology"—also advertised under other names such as "quantum scalar energy", "volcanic lava energy", and "quantum science". These products are purportedly infused with minerals that generate negative ions and are marketed as having health benefits or as a means of improving emotional well-being. The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission and various state agencies have cautioned that such products may contain radioactive material such as uranium and thorium to produce negative ions.[15][16][17][18] Radioactivity levels of these products vary, with some products found to contain levels of radiation high enough to warrant increased regulatory control, such as requiring a radioactive materials license.

- A number of alleged "anti-5G protection" products such as necklaces also received regulatory warnings. While their radioactivity levels are low, vendor recommendation to wear them all the time on body may result in an absorbed dosage exceeding safe limits.[19]

See also

- Eben Byers

- Electrical quackery

- History of radiation therapy

- Magnet therapy

- Radium Girls

- Radium fad

- Shoe-fitting fluoroscope

- Snake oil

- Negative ion products

- Radiation hormesis

References

- ^ a b Gray, Theodore (August 2004). "For That Healthy Glow, Drink Radiation!". Popular Science. Vol. 265, no. 2. p. 28. ISSN 0161-7370.

- ^ Gadbow, Daryl (4 July 2004). "State of mine: Many swear to benefits of inhaling radon". Missoulian. Retrieved 2013-09-18.

- ^ Macklis, R. M. (1990). "The radiotoxicology of Radithor. Analysis of an early case of iatrogenic poisoning by a radioactive patent medicine". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 264 (5): 619–621. doi:10.1001/jama.264.5.619. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 2366303.

- ^ Goldsmith, Barbara (2005). Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 119–120. ISBN 0-393-05137-4.

- ^ Matricon, Jean; Waysand, G. (2003). The Cold Wars: A History of Superconductivity. Rutgers University Press. p. 113. ISBN 0-8135-3295-7.

- ^ Vickery, Matthew. "A spa where patients bathe in radioactive water". BBC.

- ^ Radium Baths, Thames Star, Oct. 19, 1912, p. 2.

- ^ "At a German Health Spa, Radiation Is King". ABC News. 6 January 2006.

- ^ "Thousands of people are 'treated' with radon baths every year in Ukraine". The World.

- ^ Kabat, Geoffrey. "In Germany And Austria, Visits To Radon Health Spas Are Covered By Health Insurance". Forbes. Retrieved 2021-08-30.

- ^ Seff, Philip; Seff, Nancy R. (1996). Petrified lightning and more amazing stories from "Our fascinating earth". Chicago, Ill.: Contemporary Books. p. 18. ISBN 0-8092-3250-2.

- ^ Kelly, Bella. "Clinic Plugs Uranium Sand 'Cures'" Archived 2018-12-22 at the Wayback Machine. Miami News, July 29, 1956, pp. 1A, 14A. Retrieved on June 24, 2013.

- ^ Radium Historical Items Catalog Final Report. August 2008.

- ^ Import of Cigarette Plates Containing Source Material August 20, 1982.

- ^ Holahan, Vince (July 28, 2014). ""Negative Ion" Technology—What You Should Know". U.S. NRC Blog. U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

- ^ "Negative Ion Technology: Consumer Products and Radiation". Utah Department of Environmental Quality.

- ^ "Radioactive Consumer Products". Washington State Department of Health.

- ^ Thometz, Kristen (May 15, 2018). "State Agency Finds Trace Amounts of Radioactive Materials in Pendants". WTTW News.

- ^ "Anti-5G necklaces found to be radioactive". BBC News. 2021-12-17. Retrieved 2022-01-15.

External links

- L’histoire étonnante du Tho-Radia, by Thierry Lefebvre and Cécile Raynal (in French)

- Radioactive Quack Cures at the Museum of Oak Ridge Associated Universities