Informatics Educational Institutions & Programs

Contents

United States | |

| Value | 50 cents (0.50 US dollars) |

|---|---|

| Mass | 12.5 g |

| Diameter | 30.61 mm (1.20 in) |

| Thickness | 2.15 mm (0.08 in) |

| Edge | Reeded |

| Composition |

|

| Silver | 0.36169 troy oz |

| Years of minting | 1936 |

| Mintage | 100,055 (28,631 were melted down; the extra 55 coins were for assay) |

| Mint marks | S |

| Obverse | |

| |

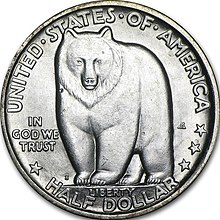

| Design | Grizzly bear |

| Designer | Jacques Schnier |

| Design date | 1936 |

| Reverse | |

| |

| Design | San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge |

| Designer | Jacques Schnier |

| Design date | 1936 |

The San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge half dollar or Bay Bridge half dollar is a commemorative fifty-cent piece struck by the United States Bureau of the Mint in 1936. One of many commemoratives issued that year, it was designed by Jacques Schnier and honors the opening of the Bay Bridge that November. One side of the coin depicts a grizzly bear, a symbol of California, and the other shows the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge, with the Ferry Building in the foreground.

Competing bills were considered by Congress in 1936: one to mark the Bay Bridge's completion that year, the other to honor both that and the Golden Gate Bridge, also under construction. The bill that only commemorated the Bay Bridge was successful, and passed into law with the signature of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. After some discussion involving the Commission of Fine Arts, which reviews coinage designs, Schnier's models were approved and the coins were struck at the San Francisco Mint.

Just over 70,000 coins were sold of the distribution mintage of 100,000, by mail, in person, and—making it the first commemorative coin to be sold on a drive-in basis—from booths at the Bay Bridge's approaches. The coins were taken off sale in February 1937, with the unsold remainder returned to the Mint for redemption and melting. The Bay Bridge half dollar catalogs in the low hundreds of dollars, depending on condition.

Background

When the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge opened in 1936, it allowed motorists, for the first time, to drive quickly and easily between San Francisco and Oakland. Ferries had operated across San Francisco Bay since 1851, but a bridge was far more convenient for automobile drivers. Politics, engineering and financing had blocked earlier proposals dating back to the 1870s; the winds and currents of the bay, and the lack of bedrock to build upon, were believed by some to make such a bridge impossible, especially since it would have to extend 8 miles (13 km). It was not until the 1930s, when with the support of President Herbert Hoover, a Californian, that the Reconstruction Finance Corporation agreed to purchase construction bonds backed by future tolls for what would be the largest and most expensive bridge of its time.[1]

Sparked by low-mintage issues which appreciated in value, the market for United States commemorative coins spiked in 1936. Until 1954, the entire mintage of such issues was sold by the government at face value to a group authorized by Congress, who then tried to sell the coins at a profit to the public. The new pieces then came on to the secondary market, and in early 1936 all earlier commemoratives sold at a premium to their issue prices. The apparent easy profits to be made by purchasing and holding commemoratives attracted many to the coin collecting hobby, where they sought to purchase the new issues.[2] Congress authorized an explosion of commemorative coins in 1936; an unprecedented fifteen were issued.[3] One coin authorized and issued in 1936 was the Cincinnati Musical Center half dollar, controlled and profited from by Thomas G. Melish—and issued to celebrate a nonexistent anniversary.[4] In addition, at the request of the groups authorized to purchase them, several coins minted in prior years were produced again, dated 1936, senior among them the Oregon Trail Memorial half dollar, first struck in 1926.[3]

By mid-1936, Congress had reacted to these practices, adding protections to commemorative coinage bills such as a requirement that all coins be struck at a single mint, rather than all three then operating as with earlier issues (the use of mint marks would force coin collectors to buy three near-identical coins to have a complete set).[5] Such a provision was present in the bill authorizing the Bay Bridge half dollar,[6] which also required that the funds generated be used towards the celebration.[7] Unlike many early commemoratives, which were struck to mark an anniversary, the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge half dollar was, like the Panama–Pacific commemorative coins, struck in order to celebrate a present-day engineering achievement.[8]

Legislation

A bill for a commemorative half dollar honoring the opening of the Bay Bridge was introduced in the United States Senate by Hiram Johnson of California on April 10, 1936. Other than referring the bill to the Committee on Banking and Currency, the Senate took no action on the bill that day;[9] it was busy with the impeachment trial of federal judge Halsted L. Ritter of Florida.[10] The Banking Committee reported back on the bill with a favorable recommendation, suggesting that the minimum number of coins to be drawn at any one time be increased from 5,000 to 25,000. The Senate considered six commemorative coin bills in a row on June 1, 1936. Four, including the Bay Bridge bill, passed without any discussion; two were deferred until later.[11]

A bill for a commemorative coin honoring the opening of the new bridges in the San Francisco Bay Area (including the Golden Gate Bridge) was introduced in the House of Representatives by Albert E. Carter of California on April 21, 1936. It was referred to the Committee on Coinage, Weights, and Measures.[12] John Cochran of Missouri reported that bill back on April 23, with a recommendation that it pass;[13] he brought the bill to the House floor on May 27, 1936. Robert F. Rich of Pennsylvania, a Republican, noted that this was about the 35th coinage bill to come forward that year and suggested that "we place on the one side of this coin the face of Mr. Farley, Democratic National Committeeman; then turn the coin over and place on the other side of it the face of Mr. Farley, the New York city committeeman; then when you flop coins you will always have the head of Farley".[14] Nevertheless, Rich did not object and the House passed the bill without further debate.[15]

On June 18, Cochran informed the House that each body had passed a different bill for the California bridge celebrations and asked that the Senate bill be considered. It was passed without debate, and the House bill was laid on the table.[16] The Senate bill for 200,000 commemorative half dollars in honor of the Bay Bridge opening became law with the signature of President Franklin D. Roosevelt on June 26, 1936.[17] A separate bill was introduced for a coin to honor the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge, but it failed to pass.[18]

Preparation

According to numismatic author Don Taxay, preparations for the coin must have begun soon after the authorization was signed, for on July 20, 1936, Franck R. Havenner, the chair of the San Francisco Citizen's Celebration Committee, wrote to Assistant Director of the Mint Mary M. O'Reilly. Havenner had some procedural questions, sent information on the selected artist for the coin, Jacques Schnier, and enclosed photographs of the chosen design. These were sent to the Commission of Fine Arts (CFA),[19] responsible under a 1921 executive order by President Warren G. Harding for rendering advisory opinions on public artworks, including coins.[20] On July 31, the CFA chair, Charles Moore, wrote to Havenner relaying the suggestion of the CFA's sculptor-member, Lee Lawrie, that the lettering in the design be made larger.[21]

After the required plaster models of the proposed coin were completed, the CFA met on September 15 to consider photographs of them. Moore sent a letter to O'Reilly, stating that the bear's nose was unlike that of a grizzly, and supplied images for Schnier's use in revising it. On the original designs, the mottoes E PLURIBUS UNUM and IN GOD WE TRUST flanked the bear to left and right: one member of the CFA, John M. Howells did not like the positioning of the latter. Correspondence among the various parties followed, since it was uncertain where it could be moved to. Eventually, Havenner telegraphed to the Mint noting that some previous commemoratives had excluded either E PLURIBUS UNUM or LIBERTY and proposing that E PLURIBUS UNUM be omitted and IN GOD WE TRUST moved to the left of the bear in its place. O'Reilly accepted this; Schnier modified his designs, and approval from the CFA and the Treasury Department soon followed.[22] Schnier's models were reduced to coin-sized hubs by the Medallic Art Company of New York.[23]

Design

According to numismatic writers Anthony Swiatek and Walter Breen, "it is a matter of guesswork which side should be called the obverse. We follow tradition like [Arlie] Slabaugh and [Don] Taxay and list the side with the bear".[24] There was criticism of the grizzly bear design at the time of release, for it was stated that the bear used as model was Monarch II, who lived 26 years in a cage in Golden Gate Park, objectors argued that such a bear was no fit symbol for Liberty, the word that appears at its feet.[24] Q. David Bowers, in his volume on commemoratives, contends that the bear was a composite of several animals seen by Schnier at the San Francisco and Oakland zoos.[25] Taxay noted that the grizzly bear is commonly used by artists to represent California, and that Schnier's was "an unusually successful treatment".[26] The four stars seen, one to the left and three to the right of the animal, lack symbolic meaning and were not present on Schnier's original sketch of the obverse.[27] The mint mark S for the San Francisco Mint flanks the bear on the left, with the artist's initials JS on its right.[24]

The other side of the coin depicts the bridge, as seen from the San Francisco side. The Ferry Building on the Embarcadero is in the foreground, with Yerba Buena Island in mid-bay, with the Berkeley Hills of the East Bay seen in the distance. A ferry boat and an ocean liner sail through the water.[28] Treasure Island, connected to Yerba Buena, is not visible as it is an artificial construction that had not yet been completed.[24] The name of the bridge and the date of striking ring the depiction.[27] The design for this side is complicated, and there are no completely flat areas.[25]

Numismatist Stuart Mosher, in his 1940 book on commemoratives, noted the Monarch II controversy and the bear motif's similarity to the California Diamond Jubilee half dollar (1925), though he deemed the bear "of secondary importance compared to the bridge design".[25] Coin author Anthony Swiatek deemed it "a lovely coin".[29] Art historian Cornelius Vermeule praised the Bay Bridge half dollar in his volume on American coins and medals, stating that no commemorative half dollar "tries animals or vistas on a grander scale than Jacques Schnier's coin for California's giant new bridge in 1936".[30] Vermeule stated "the temptation to show comprehensive views of harbors on coins has existed ever since Nero adorned a sestertius with Rome's basin at Ostia [...]. Schnier's grand view from San Francisco to Berkeley is comparable to geography on coins and medals of the sixteenth or seventeenth century [...]. In being so bold it deserves praise for the aesthetic excitement it generates and its artistic success. The bear is a poignant combination of furry power and animal, specifically ursine, sympathies."[31]

Production, distribution and collecting

A total of 100,055 Bay Bridge half dollars were struck at the San Francisco Mint in November 1936, with 55 pieces set aside for transmission to Philadelphia for examination and testing at the following year's meeting of the Assay Commission.[32] Although they were struck no differently than the rest of the coins minted, the first 200 coins that were struck were reserved for presentation purposes. Of these coins, the 22 that were not presented were later sold to collectors with documentation of their early striking.[33] Only half the authorized mintage of 200,000 was struck; numismatic author Arlie Slabaugh Jr. deemed that decision wise, as profit-minded collectors and investors would not have favored a higher mintage. The bridge had opened on November 12, 1936 with a celebration that continued for three days[34] but the coins arrived too late for that, and went on sale about a week later. Distribution of the coins was handled by a group of banks known as the San Francisco Clearing House Association, or they could be purchased by mail from celebration organizers' offices on Market Street at $1.65 each, with a discount for ten or more.[32] Booths were erected near the bridge entrances from which motorists could purchase the new coin for $1.50 without needing to leave their vehicles.[29] Another account states that the coin was sold from the tollbooths.[32] In either event, it was the first time that a commemorative coin had been made available on a drive-in basis.[17]

In late January 1937, Lawrence M. Giannini, head of the finance committee distributing the coins, announced that sales would end on February 15, and that the remaining coins would be returned to the Mint for redemption and melting.[35] By this time, sales had ground to a halt. A total of 71,369 half dollars were sold; the remainder, 28,631 coins, was returned to the Mint and were melted.[29]

By 1940, the market price for the Bay Bridge half dollar remained at $1.50. It gradually rose thereafter and at the peak of the 1980 commemorative coin boom sold for $240; in 1990, market prices ranged from $120 to $560, depending on condition.[36] The Mega Red edition of R.S. Yeoman's A Guide Book of United States Coins, published in 2018, lists the Bay Bridge piece for between $145 and $340, depending on condition.[37] An exceptional specimen sold for $21,850 in 2004.[38]

In 1986, in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the bridge coin issue, 1,000 of the half dollars were placed into holders which were autographed by Schnier, numbered, and sealed in plastic.[23] This was for a coin dealer;[29] the coins were purchased on the open market and were not from unsold remainders.[17]

References

- ^ "Bay Bridge history". The San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge Seismic Safety Projects. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2019.

- ^ Bowers, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Yeoman, pp. 1068–1077.

- ^ Swiatek, p. 304.

- ^ Flynn, p. 116.

- ^ Bowers, p. 397.

- ^ Flynn, p. 356.

- ^ "1936 S Bay Bridge 50C MS Silver Commemoratives". www.ngccoin.com. Numismatic Guaranty Corporation (NGC). Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ 1936 Congressional Record, Vol. 82, Page 5356 (April 10, 1936), available here

- ^ 1936 Congressional Record, Vol. 82, Page 5321–5349 (April 10, 1936), available here

- ^ 1936 Congressional Record, Vol. 82, Page 8439–8441 (June 1, 1936), available here

- ^ 1936 Congressional Record, Vol. 82, Page 5828 (April 21, 1936), available here

- ^ "Authorize the coinage of 50-cent pieces in commemoration of the completion of the bridges in the San Francisco Bay Area". United States House of Representatives. April 23, 1936.

- ^ 1936 Congressional Record, Vol. 82, Page 8141 (May 27, 1936), available here

- ^ 1936 Congressional Record, Vol. 82, Page 8141–8142 (May 27, 1936), available here

- ^ 1936 Congressional Record, Vol. 82, Page 9997 , available here}

- ^ a b c Bowers, p. 399.

- ^ Slabaugh, p. 131.

- ^ Taxay, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Taxay, pp. v–vi.

- ^ Taxay, p. 233.

- ^ Taxay, pp. 233–235.

- ^ a b Brothers, Eric (October 2014). "One hit wonders: Jacques Schnier". The Numismatist: 67.

- ^ a b c d Swiatek & Breen, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Bowers, p. 398.

- ^ Taxay, p. 232.

- ^ a b Flynn, p. 52.

- ^ Flynn, pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b c d Swiatek, p. 373.

- ^ Vermeule, p. 199.

- ^ Vermeule, pp. 199–200.

- ^ a b c Flynn, p. 53.

- ^ "Bay Bridge Half Dollar". CoinSite. 30 November 2013. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ Slabaugh, pp. 130–131.

- ^ "Unsold San Francisco-Oakland coins melted". The Numismatist: 208. March 1937.

- ^ Bowers, p. 400.

- ^ Yeoman, p. 1088.

- ^ Flynn, p. 54.

Sources

- Bowers, Q. David (1992). Commemorative Coins of the United States: A Complete Encyclopedia. Wolfeboro, NH: Bowers and Merena Galleries, Inc. ISBN 978-0-943161-35-8.

- Flynn, Kevin (2008). The Authoritative Reference on Commemorative Coins 1892–1954. Roswell, GA: Kyle Vick. OCLC 711779330.

- Slabaugh, Arlie R. (1975). United States Commemorative Coinage (second ed.). Racine, WI: Whitman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-307-09377-6.

- Swiatek, Anthony (2012). Encyclopedia of the Commemorative Coins of the United States. Chicago, IL: KWS Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9817736-7-4.

- Swiatek, Anthony & Breen, Walter (1981). The Encyclopedia of United States Silver & Gold Commemorative Coins, 1892 to 1954. New York, NY: Arco Publishing. ISBN 978-0-668-04765-4.

- Taxay, Don (1967). An Illustrated History of U.S. Commemorative Coinage. New York, NY: Arco Publishing. ISBN 978-0-668-01536-3.

- Vermeule, Cornelius (1971). Numismatic Art in America. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-62840-3.

- Yeoman, R. S. (2018). A Guide Book of United States Coins (Mega Red 4th ed.). Atlanta, GA: Whitman Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-0-7948-4580-3.

External links

Media related to San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge half dollar at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge half dollar at Wikimedia Commons