Informatics Educational Institutions & Programs

Contents

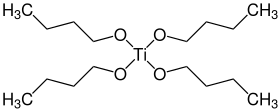

gas phase structure

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Titanium(IV) butoxide

| |

| Other names | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.024.552 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 2920 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C16H36O4Ti | |

| Molar mass | 340.32164 |

| Appearance | COLORLESS TO LIGHT-YELLOW LIQUID |

| Odor | weak alcohol-like[1] |

| Density | 0.998 g/cm3[1] |

| Melting point | -55 °C[1] |

| Boiling point | 312 °C[1] |

| decomposes[1] | |

| Solubility | most organic solvents except ketones[1] |

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.486[1] |

| Thermochemistry | |

Heat capacity (C)

|

711 J/(mol·K)[2] |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

-1670 kJ/mol[2] |

| Hazards | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

3122 mg/kg (rat, oral) and 180 mg/kg (mouse, intravenal).[1] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Titanium butoxide is a metal alkoxide with the formula Ti(OBu)4 (Bu = –CH2CH2CH2CH3). It is a colorless odorless liquid although aged samples can appear yellowish. Owing to hydrolysis, samples have a weak alcohol-like odor. It is soluble in many organic solvents.[1][3] Decomposition in water is not hazardous, and therefore titanium butoxide is often used as a liquid source of titanium dioxide, which allows deposition of TiO2 coatings of various shapes and sizes down to the nanoscale.[4][5]

Titanium butoxide is often used to prepare titanium oxide materials and catalysts.[6][7][citation needed]

Structure and synthesis

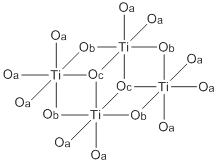

Like most titanium alkoxides (exception: titanium isopropoxide), Ti(OBu)4 is not a monomer but exists as a cluster (see titanium ethoxide). Nonetheless it is often depicted as a simple monomer.[citation needed]

It is produced by treating titanium tetrachloride with butanol:

- TiCl4 + 4 HOBu → Ti(OBu)4 + 4 HCl

The reaction requires base to proceed to completion.[citation needed]

Reactions

Like other titanium alkoxides, titanium butoxide exchanges alkoxide groups:

- Ti(OBu)4 + HOR → Ti(OBu)3(OR) + HOBu

- Ti(OBu)3(OR) + HOR → Ti(OBu)2(OR)2 + HOBu

etc. For this reason, titanium butoxide is not compatible with alcohol solvents.

Analogous to the alkoxide exchange, titanium butoxide hydrolyzes readily. The reaction details are complex, but the overall process can be summarized with this balanced equation.

- Ti(OBu)4 + 2 H2O → TiO2 + 4 HOBu

Diverse oxo-alkoxo intermediates have been trapped and characterized.[8] Pyrolysis also affords the dioxide:

- Ti(OBu)4 → TiO2 + 2 Bu2O

Titanium butoxide reacts with alkylcyclosiloxanes. With ocatamethylcyclotetrasiloxane it produces dibutoxydimethylsilane, 1,5-dibutoxyhexamethyltrisiloxane, 1,7-dibutoxyoctamethyltetrasiloxane, 1,3-dibutoxytetramethyldisiloxane and polymers. With hexamethylcyclotrisiloxane it also produces dibutoxydimethylsilane.[9]

Safety

LD50 is 3122 mg/kg (rat, oral) and 180 mg/kg (mouse, intravenal).[citation needed]

Titanium butoxide is a corrosive, flammable liquid which reacts violently with oxidizing materials. It is incompatible with sulfuric and nitric acids, inorganic hydroxides and peroxides, bases, amines, amides, isocyanates and boranes. It is irritating to skin and eyes, and causes nausea and vomiting if swallowed. LD50 is 3122 mg/kg (rat, oral) and 180 mg/kg (mouse, intravenal); flash point is 77 °C. When heated it emits irritating fumes, which form explosive mixtures with air at concentrations above 2 vol%.[citation needed]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Butyl titanate. pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- ^ a b c Tetrabutyl titanate. nist.gov

- ^ Pohanish, Richard P.; Greene, Stanley A. (2009). Wiley Guide to Chemical Incompatibilities. John Wiley & Sons. p. 1010. ISBN 978-0-470-52330-8.

- ^ a b Wang, Cui (2015). "Hard-templating of chiral TiO2 nanofibres with electron transition-based optical activity". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 16 (5): 054206. Bibcode:2015STAdM..16e4206W. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/16/5/054206. PMC 5070021. PMID 27877835.

- ^ Wu, Limin; Baghdachi, Jamil (2015). Functional Polymer Coatings: Principles, Methods, and Applications. Wiley. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-118-88303-7.

- ^ Qin, Qing; Zhao, Yun; Schmallegger, Max; Heil, Tobias; Schmidt, Johannes; Walczak, Ralf; Gescheidt-Demner, Georg; Jiao, Haijun; Oschatz, Martin (2019). "Enhanced Electrocatalytic N2 Reduction via Partial Anion Substitution in Titanium Oxide–Carbon Composites". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 58 (37): 13101–13106. doi:10.1002/anie.201906056. hdl:21.11116/0000-0004-023B-8. PMID 31257671. S2CID 195760017.

- ^ Xiang, Quanjun; Yu, Jiaguo; Jaroniec, Mietek (2012). "Synergetic Effect of MoS2 and Graphene as Cocatalysts for Enhanced Photocatalytic H2 Production Activity of TiO2 Nanoparticles". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 134 (15): 6575–6578. doi:10.1021/ja302846n. PMID 22458309.

- ^ Weymann-Schildknetch, Sandrine; Henry, Marc (2001). "Mechanistic Aspects of the Hydrolysis and Condensation of Titanium Alkoxides Complexed by Tripodal Ligands". Journal of the Chemical Society, Dalton Transactions (16): 2425–2428. doi:10.1039/b103398k.

- ^ K. A. Andrianov; Sh. V. Pichkhadze; V. V. Komarova; Ts. N. Vardosanidze (1962). "Reactions of organocyclosiloxanes with tetrabutyl orthotitanate". Bulletin of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR Division of Chemical Science. 11 (5): 776–779. doi:10.1007/BF00905301. ISSN 0568-5230.