Informatics Educational Institutions & Programs

Contents

→Life and death of Philippe Pot: images size |

|||

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''Tomb of Philippe Pot''' is a life-sized [[Funerary art|funerary monument]] commissioned in 1477 by [[Philippe Pot]] for his planned burial place in the chapel of Saint-Jean-Baptiste in [[Cîteaux Abbey]], near [[Dijon]], France. His [[effigy]] shows him recumbent on a slab with his hands joined in prayer, wearing |

The '''Tomb of Philippe Pot''' is a life-sized [[Funerary art|funerary monument]] commissioned in 1477 by [[Philippe Pot]] for his planned burial place in the chapel of Saint-Jean-Baptiste in [[Cîteaux Abbey]], near [[Dijon]], France. His [[effigy]] shows him recumbent on a slab with his hands joined in prayer, wearing armour and a heraldic [[tunic]]. He is carried by eight [[pleurants]] (mourners), dressed in black hoods and act as [[pallbearer]]s carrying Philippe towards his grave. |

||

Philippe commissioned the tomb when he was around 49 years old, some 13 years before his death in 1493. He was a godson of [[Philip the Good]] and became a [[Knight of the Golden Fleece]] and the [[Seneschal|Grand Seneschal]] of Burgundy. He served under both |

Philippe commissioned the tomb when he was around 49 years old, some 13 years before his death in 1493. He was a godson of [[Philip the Good]] and became a [[Knight of the Golden Fleece]] and the [[Seneschal|Grand Seneschal]] of Burgundy. He served under both the two last Dukes of Burgundy: Philip the Good and [[Charles the Bold]], until the latter's defeat by the French king [[Louis XI]] at the [[battle of Nancy]] in 1477, after which he served under both Louis XI and [[Charles VIII of France|Charles VIII]]. The detailed inscriptions running along each sides of the slab detail his importance as a military leader and diplomat. |

||

The tomb is made of [[limestone]], paint, gold and lead. It is recorded as completed in 1480 but there is no mention of its designers or craftsmen. Art historians generally cite [[Antoine Le Moiturier]] as the most likely designer of the pleurants, based on circumstantial evidence including similarities to his other works.<ref name="s41">Jugie (2019), p. 41</ref> The monument was stolen during the [[French Revolution]], and after changing hands a number of times was placed in the 19th century in a private garden in Dijon. It has been in the collection of the [[Louvre|Musée du Louvre]] since 1899, where it is on permanent display in room 210. Between 2016 and 2018 it underwent a major technical examination and restoration. |

The tomb is made of [[limestone]], paint, gold and lead. It is recorded as completed in 1480 but there is no mention of its designers or craftsmen. Art historians generally cite [[Antoine Le Moiturier]] as the most likely designer of the pleurants, based on circumstantial evidence including similarities to his other works.<ref name="s41">Jugie (2019), p. 41</ref> The monument was stolen during the [[French Revolution]], and after changing hands a number of times was placed in the 19th century in a private garden in Dijon. It has been in the collection of the [[Louvre|Musée du Louvre]] since 1899, where it is on permanent display in room 210. Between 2016 and 2018 it underwent a major technical examination and restoration. |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

[[Philippe Pot]] was born in 1428 near [[Beaune]] in eastern France, as a godson of [[Philip the Bold]].<ref name="p&p289">Panofski; Panofsky (1968), p. 289</ref> He was raised and educated at the [[Duchy of Burgundy|Burgundian court]]. He became a ''[[Lord|seigneur]]'' of [[La Rochepot|La Roche]] and [[Thorey-sur-Ouche]], a [[Knight of the Golden Fleece]], and a [[Seneschal|Grand Seneschal]] of Burgundy. He served under the two last Dukes of Burgundy: [[Philip the Good]] and [[Charles the Bold]]. After the latter's defeat by [[Louis XI]] at the Battle of Nancy in 1477, the dynasty died out. Philippe was expelled from the [[Citadel of Lille]] in 1477, having been tried for perjury amongst other charges, but there-after served under two French kings: Louis and [[Charles VIII of France|Charles VIII]].<ref name="j40" /> |

[[Philippe Pot]] was born in 1428 near [[Beaune]] in eastern France, as a godson of [[Philip the Bold]].<ref name="p&p289">Panofski; Panofsky (1968), p. 289</ref> He was raised and educated at the [[Duchy of Burgundy|Burgundian court]]. He became a ''[[Lord|seigneur]]'' of [[La Rochepot|La Roche]] and [[Thorey-sur-Ouche]], a [[Knight of the Golden Fleece]], and a [[Seneschal|Grand Seneschal]] of Burgundy. He served under the two last Dukes of Burgundy: [[Philip the Good]] and [[Charles the Bold]]. After the latter's defeat by [[Louis XI]] at the Battle of Nancy in 1477, the dynasty died out. Philippe was expelled from the [[Citadel of Lille]] in 1477, having been tried for perjury amongst other charges, but there-after served under two French kings: Louis and [[Charles VIII of France|Charles VIII]].<ref name="j40" /> |

||

[[Tomb of Philip the Bold|Philip's tomb]] was commissioned in the late 14th century as the first of the Burgundian style tombs. He hired the Dutch sculptor [[Claus Sluter]], whose distinctive style in placing mourners around effigy was often copied over the following centuries. Philippe's tomb follows the style of Philip the Bold's, which was commissioned in the late 14th century as the first of the now well |

[[Tomb of Philip the Bold|Philip's tomb]] was commissioned in the late 14th century as the first of the Burgundian style tombs. He hired the Dutch sculptor [[Claus Sluter]], whose distinctive style in placing mourners around effigy was often copied over the following centuries. Philippe's tomb follows the style of Philip the Bold's, which was commissioned in the late 14th century as the first of the now well-known Burgundian style tombs.<ref name = "Sadler22">Sadler (2015), p. 22</ref><ref>Hourihane (2012), p. 357</ref> |

||

[[File:Effigie du chevalier Philippe Pot (détails)..jpg|upright=1.2|thumb|Philippe Pot's effigy, with head rested on a cushion, eyes open and hands clasped in prayer.]] |

[[File:Effigie du chevalier Philippe Pot (détails)..jpg|upright=1.2|thumb|Philippe Pot's effigy, with head rested on a cushion, eyes open and hands clasped in prayer.]] |

||

The tomb is first recorded on August |

The tomb is first recorded on 28 August 1480, when Philippe paid the abbot of [[Cîteaux Abbey]], Jean de Cirey, one thousand [[livres]] for a burial place. Although the dates of its construction are not known, it is generally assumed to have been between 1480 and 1483, given the inscriptions record events after the January 1477 death of Charles the Bold at the [[battle of Nancy]], and mention Louis XI as king.<ref name="s20">Jugie (2019), p. 20</ref> |

||

It was placed in the [[chapel]] of Saint-Jean-Baptiste, at the corner of the south [[transept]] and the [[ambulatory]].<ref name="s20" /><ref>Sadler (2015), p. xi</ref> Philippe's motto "Tant L. vaut, était" was painted in several locations within his chapel, and the tomb was positioned to the left of the altar so that his feet would point towards the east, as was customary for a secular burial.<ref name="s20" /> The date of death would have been left blank during its construction. The current date was probably added in the 19th century, but erroneously gives the year of death 1494 (rather than 1493), and does not give the month.<ref name="s20" /> |

It was placed in the [[chapel]] of Saint-Jean-Baptiste, at the corner of the south [[transept]] and the [[ambulatory]].<ref name="s20" /><ref>Sadler (2015), p. xi</ref> Philippe's motto "Tant L. vaut, était" was painted in several locations within his chapel, and the tomb was positioned to the left of the altar so that his feet would point towards the east, as was customary for a secular burial.<ref name="s20" /> The date of death would have been left blank during its construction. The current date was probably added in the 19th century, but erroneously gives the year of death 1494 (rather than 1493), and does not give the month.<ref name="s20" /> |

||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

===Effigy=== |

===Effigy=== |

||

Philippe lies on a limestone plate or slab, dressed in a [[tunic]] and silver |

Philippe lies on a limestone plate or slab, dressed in a [[tunic]] and silver armour covered with a [[Gilding|gilded]] breastplate and a [[knight]]ly helmet.<ref name="j40">Jugie (2010), p. 40</ref> His head rests on a cushion, his eyes are open and his hands are clasped in prayer. A sword lies to his side while his feet rest on an animal that maybe either a lion or dog.<ref name="s14" /><ref name="j52">Jugie (2010), p. 52</ref> The [[coat of arms]] on his shield are painted in gold, red and the black, and show the insignia of his ancestral families of Pot, Courtiamble, Anguissola, Blaisy, Guénant and Nesles et Montagu.<ref name="j40" /> Unusually the effigy does not contain any of the [[angel]]s usually seen in contemporary Northern European tombs, where they often guide the deceased to the afterlife.<ref name="j40" /> |

||

===Pleurants=== |

===Pleurants=== |

||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

Philippe Pot's tomb was the last major tomb of the Burgundians<ref name="j52"/> but had a significant influence on later funerary artworks. The sculpture transformed the conventional size and placement of pleurants, which since the tomb of Philip the Good had been relatively small figures standing in a [[Niche (architecture)|niche]] in the sarcophagus' lower [[Register (art)|register]]. The motif of eight mourners carrying an effigy's slab can be seen on the tombs of Louis de Savoisy (d. 1515) and Jacques de Mâlain (d. 1527).<ref name="s36">Jugie (2019), p. 36</ref><ref>Sadler (2015), p. 23</ref> |

Philippe Pot's tomb was the last major tomb of the Burgundians<ref name="j52"/> but had a significant influence on later funerary artworks. The sculpture transformed the conventional size and placement of pleurants, which since the tomb of Philip the Good had been relatively small figures standing in a [[Niche (architecture)|niche]] in the sarcophagus' lower [[Register (art)|register]]. The motif of eight mourners carrying an effigy's slab can be seen on the tombs of Louis de Savoisy (d. 1515) and Jacques de Mâlain (d. 1527).<ref name="s36">Jugie (2019), p. 36</ref><ref>Sadler (2015), p. 23</ref> |

||

it was photographed a number of times in the mid-19th century, before it was acquired by the Louvre.<ref name="s25" /> It was depicted by the German [[Expressionist]] painter [[Paula Modersohn-Becker]],<ref name="j34">Jugie (2010), p. 34</ref> and in 2010 by the |

it was photographed a number of times in the mid-19th century, before it was acquired by the Louvre.<ref name="s25" /> It was depicted by the German [[Expressionist]] painter [[Paula Modersohn-Becker]],<ref name="j34">Jugie (2010), p. 34</ref> and in 2010 by the sculptor [[Matthew Day Jackson]] in an installation showing astronauts in wood and plastic carrying a glass containing a human skeleton.<ref>"[https://www.peterblumgallery.com/exhibitions/matthew-day-jackson2/press-release Matthew Day Jackson]", 2010. Peter Blum Gallery. Retrieved 27 December 2022</ref><ref> |

||

Spears, Dorothy. "[https://www.huffpost.com/entry/matthew-day-jackson-artis_b_761002 Matthew Day Jackson: Artist as Stuntman]". ''[[HuffPost]]'', 18 October 2010. Retrieved 27 December 2022</ref> |

Spears, Dorothy. "[https://www.huffpost.com/entry/matthew-day-jackson-artis_b_761002 Matthew Day Jackson: Artist as Stuntman]". ''[[HuffPost]]'', 18 October 2010. Retrieved 27 December 2022</ref> |

||

| Line 94: | Line 94: | ||

==Sources== |

==Sources== |

||

{{refbegin|30em}} |

{{refbegin|30em}} |

||

* Antoine, Elisabeth. ''Art from the Court of Burgundy: The Patronage of Philip the Bold and John the Fearless, |

* Antoine, Elisabeth. ''Art from the Court of Burgundy: The Patronage of Philip the Bold and John the Fearless, 1364–1419''. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, 2005. {{isbn|978-2-7118-4864-5}} |

||

* Chabeuf, Henri. ''Jean de La Huerta, Antoine Le Moiturier et le tombeau de Jean sans Peur, Dijon''. Darantière, 1891 |

* Chabeuf, Henri. ''Jean de La Huerta, Antoine Le Moiturier et le tombeau de Jean sans Peur, Dijon''. Darantière, 1891 |

||

* De Winter, Patrick M. "Art from the Duchy of Burgundy". ''The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art'', vol. 74, no. 10, 1987. 406–449. {{JSTOR|25160010}} |

* De Winter, Patrick M. "Art from the Duchy of Burgundy". ''The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art'', vol. 74, no. 10, 1987. 406–449. {{JSTOR|25160010}} |

||

Revision as of 13:59, 29 January 2023

| Tomb of Philippe Pot | |

|---|---|

| |

| Material | Limestone, paint, lead, gold |

| Size |

|

| Created | 1477–1480 |

| Period/culture | Northern Renaissance |

| Present location | Musée du Louvre, Paris |

| Identification | RF 795 |

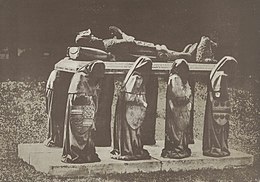

The Tomb of Philippe Pot is a life-sized funerary monument commissioned in 1477 by Philippe Pot for his planned burial place in the chapel of Saint-Jean-Baptiste in Cîteaux Abbey, near Dijon, France. His effigy shows him recumbent on a slab with his hands joined in prayer, wearing armour and a heraldic tunic. He is carried by eight pleurants (mourners), dressed in black hoods and act as pallbearers carrying Philippe towards his grave.

Philippe commissioned the tomb when he was around 49 years old, some 13 years before his death in 1493. He was a godson of Philip the Good and became a Knight of the Golden Fleece and the Grand Seneschal of Burgundy. He served under both the two last Dukes of Burgundy: Philip the Good and Charles the Bold, until the latter's defeat by the French king Louis XI at the battle of Nancy in 1477, after which he served under both Louis XI and Charles VIII. The detailed inscriptions running along each sides of the slab detail his importance as a military leader and diplomat.

The tomb is made of limestone, paint, gold and lead. It is recorded as completed in 1480 but there is no mention of its designers or craftsmen. Art historians generally cite Antoine Le Moiturier as the most likely designer of the pleurants, based on circumstantial evidence including similarities to his other works.[1] The monument was stolen during the French Revolution, and after changing hands a number of times was placed in the 19th century in a private garden in Dijon. It has been in the collection of the Musée du Louvre since 1899, where it is on permanent display in room 210. Between 2016 and 2018 it underwent a major technical examination and restoration.

Life and death of Philippe Pot

Philippe Pot was born in 1428 near Beaune in eastern France, as a godson of Philip the Bold.[2] He was raised and educated at the Burgundian court. He became a seigneur of La Roche and Thorey-sur-Ouche, a Knight of the Golden Fleece, and a Grand Seneschal of Burgundy. He served under the two last Dukes of Burgundy: Philip the Good and Charles the Bold. After the latter's defeat by Louis XI at the Battle of Nancy in 1477, the dynasty died out. Philippe was expelled from the Citadel of Lille in 1477, having been tried for perjury amongst other charges, but there-after served under two French kings: Louis and Charles VIII.[3]

Philip's tomb was commissioned in the late 14th century as the first of the Burgundian style tombs. He hired the Dutch sculptor Claus Sluter, whose distinctive style in placing mourners around effigy was often copied over the following centuries. Philippe's tomb follows the style of Philip the Bold's, which was commissioned in the late 14th century as the first of the now well-known Burgundian style tombs.[4][5]

The tomb is first recorded on 28 August 1480, when Philippe paid the abbot of Cîteaux Abbey, Jean de Cirey, one thousand livres for a burial place. Although the dates of its construction are not known, it is generally assumed to have been between 1480 and 1483, given the inscriptions record events after the January 1477 death of Charles the Bold at the battle of Nancy, and mention Louis XI as king.[6]

It was placed in the chapel of Saint-Jean-Baptiste, at the corner of the south transept and the ambulatory.[6][7] Philippe's motto "Tant L. vaut, était" was painted in several locations within his chapel, and the tomb was positioned to the left of the altar so that his feet would point towards the east, as was customary for a secular burial.[6] The date of death would have been left blank during its construction. The current date was probably added in the 19th century, but erroneously gives the year of death 1494 (rather than 1493), and does not give the month.[6]

Attribution

Philippe' commissioned of his tomb in 1477 some 14 years before his eventual death 1493, reflects his desire to convey to prosperity his change in allegiance from the Duke of Burgundy to Louis XI after the battle of Nancy that year. His wish was for a monument to stand over his grave Cîteaux Abbey. It is probable that he would have first worked with an artist, likely a painter, to agree an overall design, and then hired stonemasons, sculptors and craftsmen to build the tomb.[8]

Art historians have not identified the artists or craftsmen responsible for designing or building the tomb. Moiturier (active 1482–1502) is often suggested as likely to have designed the pleurants, given the similarity of their facial types and the solid and rigid rendering of their clothing to the Mourners of Dijon.[9][10] Guillaume Chandelier has been suggested as involved, although with little supporting evidence.[11]

Art historians generally distinguish the conventional design of the effigy, and the expressive form of the mourners and the inventive placing of the slab on narrow points above each of their shoulders.[8][12] While it is possible that an artist who was both a painter and sculptor oversaw the tomb's completion, the variation of degree in the quality of sculpture indicates a number of hands. The art historian Robert Marcoux notes that parts of the sculpture are so vaguely described that it is unlikely that a master painter was involved in their completion.[13]

Description

Effigy

Philippe lies on a limestone plate or slab, dressed in a tunic and silver armour covered with a gilded breastplate and a knightly helmet.[3] His head rests on a cushion, his eyes are open and his hands are clasped in prayer. A sword lies to his side while his feet rest on an animal that maybe either a lion or dog.[14][15] The coat of arms on his shield are painted in gold, red and the black, and show the insignia of his ancestral families of Pot, Courtiamble, Anguissola, Blaisy, Guénant and Nesles et Montagu.[3] Unusually the effigy does not contain any of the angels usually seen in contemporary Northern European tombs, where they often guide the deceased to the afterlife.[3]

Pleurants

The eight mourners are slightly less than life-sized, measuring between 134 cm (53 in) and 144 cm (57 in) in height.[16] This height allows the recumbent figure to align with the viewer's line of sight.[14] They are carved in black stone and positioned in the lower register, carrying Philippe's slab on their shoulders.[17][18] They wear full-length black-hooded cloaks and shoulder-length hoods mostly covering their faces.[14] The hoods identify the mourners as laity playing a ceremonial rite that lasted in the region from the 13th to the 16th century.[19] Although mourners with black hooded do not often appear in contemporary sculpture or painting, they appear in well known works such as the tomb of Philippe Dagobert (d. 1235)e, and the c. 1452–1460 "Office of the Dead" miniature from Jean Fouquet's illuminated manuscript the "Hours of Étienne Chevalier".

Each mourner bears a gilded heraldic shield, each individually designed and referring to Philippe's lineage, making the monument of the "Kinship tomb" type.[20] When identifying the heraldry, the art historian Sophie Jugie names the mourners in order of those on Philipp's left (from his head down) mourners 1–5 and his right mourners 5–8. Using this annotation, the shields represent (1) the combined shields of Guillaume III Pot and Raguenonde Guénant (2) the Cortiambles family (3) the Anguissola family (4) de Blaisy (5) de Montagus (6) de Nesle (7) unidentified and (8) unidentified.[21]

Their weighty and austere poses gives the impression of the slow movement of a funeral procession.[22] Although their faces are covered and thus do not have individualised facial characteristics, they have different poses, heraldic shields and folded drapes.[14][23] The folds of the clothing are angular and rigid, and seem influenced by the works of mid-15th century Early Netherlandish painters such as Rogier van der Weyden, likely through engravings known to have been circulating through Dijon at the time. Other potential sources include the relief of four monks with covered heads on a short side of the tomb of Pierre de Bauffremont (d. 1472), commissioned in 1453 for his planned burial in Dijon,[24] and a near contemporary tomb in Semur-en-Auxois likely known to Phillipe.[25]

-

Mourners in a niche, tomb of John the Fearless, attributed to Juan de la Huerta, c. 1406

-

Entombment, attributed to Antoine Le Moiturier, 1490. Notre-Dame Collegiate Church of Semur-en-Auxois.[26]

Inscriptions

The extensive carved inscriptions on the edges of the slab are in Gothic script.[27] They are written in three rows, with each beginning on the right side of the head of effigy and ending behind his head. The text outlines his career with Philip the Good and Charles the Bold, as well as his reasons for switching sides to serve under Louis XI and Charles VIII following the Burgundian's defeat at the battle of Nancy in 1477.[27]

Provenance

The tomb's provenance is complex and involves a number of early modern period state and private owners and locations, and has only been fully pieced together since the mid-20th century.[2] It is first mentioned as completed in 1649 by Pierre Palliot, a bookseller and printer in Dijon, when he described the coats of arms and the inscriptions. The antiquarian and collector François Roger de Gaignières made a number of drawings between 1699 and 1700, which are lost and known only from copies by Louis Boudan (fl. 1687–1709) but contain a number of inaccuracies.[29] The tomb was nationalised during the French Revolution when all church property was transferred to the French State.[2] Sometime between 1791 and 1793 François Devosge, an artist and director of the Dijon School of Drawing, was charged with moving it to the Benedictine abbey in Saint-Bénigne.[30]

It is next mentioned in September 1808 when it was acquired for fifty-three livres by count Richard de Vesvrotte, lord of Ruffey-lès-Beaune, following a legal case against the French state.[30] He placed it in the garden of the Hôtel de Ruffey, under trees at his townhouse on 33 rue Berbisey, Dijon.[30][31]

Richard's son Pierre sold the townhouse in 1850 and relocated the tomb to the Château de Vesvrotte in Beire-le-Châtel, Côte-d'Or,[33] where it was again placed in an outdoor garden. It was photographed for the first time in a series of photolithographs commissioned by Pierre's son Alphonse Richard de Vesvrotte. They were published in 1863, and inspired Charles Édouard de Beaumont's 1875 painting Au solei (or At the Tomb of Philippe Pot"), which shows a couple laying at the foot of the tomb in a meadow surrounded by trees.[31][34]

The Vesvrotte's tried to sell the tomb after Richard's death in 1873. The French state attempted to block this by claiming that the tomb was by now public property, a claim rejected in 1886 by a Dijon court in a decision that gave full ownership to Pierre's son, Armand de Vesvrotte.[28][34] In August that year the French state claimed ownership as an object of national historical importance.[35] It was acquired for the Louvre in 1899 by the intermediator Charles Mannheim.[31]

Condition and restorations

The tomb has been cleaned and restored number of times in the 19th century, as evidence by comparison to contemporary reproductions, including an engraving that shows Philippe's fingers as badly damaged.[31] There are records of Philippe's feet and the resting animal beside them that were repaired before 1816. Some the letters and words on the inscription were restored before 1880 by the archivist Jean-Baptiste Peincedé.[35]

The tomb underwent a major restoration between 2018 and 2019 in project lead by Sophie Jugie, director of the Department of Sculptures at the Louvre.[36] It had been in poor condition, covered by accumulated layers of brown dirt around the heraldry and layers of gloss and polyvinyl alcohol from earlier cleanings. The restoration was preceded by an in-depth technical analysis conducted between 2016 and 2017 by the Center for Research and Restoration of Museums of France (C2RMF).[37] Surface layers of bleach, gloss and brown fouling of the blazons were removed, and the bare stone was cleaned, and additions from earlier restorations were removed.[37]

Imitations and replicas

Philippe Pot's tomb was the last major tomb of the Burgundians[15] but had a significant influence on later funerary artworks. The sculpture transformed the conventional size and placement of pleurants, which since the tomb of Philip the Good had been relatively small figures standing in a niche in the sarcophagus' lower register. The motif of eight mourners carrying an effigy's slab can be seen on the tombs of Louis de Savoisy (d. 1515) and Jacques de Mâlain (d. 1527).[19][38]

it was photographed a number of times in the mid-19th century, before it was acquired by the Louvre.[30] It was depicted by the German Expressionist painter Paula Modersohn-Becker,[39] and in 2010 by the sculptor Matthew Day Jackson in an installation showing astronauts in wood and plastic carrying a glass containing a human skeleton.[40][41]

References

- ^ Jugie (2019), p. 41

- ^ a b c Panofski; Panofsky (1968), p. 289

- ^ a b c d Jugie (2010), p. 40

- ^ Sadler (2015), p. 22

- ^ Hourihane (2012), p. 357

- ^ a b c d Jugie (2019), p. 20

- ^ Sadler (2015), p. xi

- ^ a b Marcoux (2003), p. 121

- ^ "Base Joconde: Tomb of Philip Pot, Grand Seneschal of Burgundy, French Ministry of Culture. (in French)

- ^ Hourihane (2012), p. 40

- ^ Hofstatter (1968), pp. 137, 256

- ^ Jugie (2019), p. 42

- ^ Marcoux (2003), pp. 124, 125

- ^ a b c d Jugie (2019), p. 14

- ^ a b Jugie (2010), p. 52

- ^ Jugie (2019), p. 11

- ^ Chabeuf (1891), pp. 116–124

- ^ Jugie (2019), p. 38

- ^ a b Jugie (2019), p. 36

- ^ McGee Morganstern (2000), p. 8

- ^ Jugie (2019), pp. 12–13

- ^ Mayade, Stéphanie. "Tombeau de Philippe Pot – Musée du Louvre, Paris". Musardises en dépit du bon sens, 5 January 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2019

- ^ Marcoux (2003), p.125

- ^ Marcoux (2003), p. 122

- ^ Marcoux (2003), pp. 126–127

- ^ Jugie (2019), p. 39

- ^ a b Jugie (2019), p. 16

- ^ a b Panofski; Panofsky (1968), p. 295

- ^ Jugie (2019), pp. 20, 22–23

- ^ a b c d Jugie (2019), p. 25

- ^ a b c d Sterling & Salinger (1966), p. 158

- ^ Panofski; Panofsky (1968), pp. 287–289

- ^ Panofski; Panofsky (1968), p. 292

- ^ a b Jugie (2019), p. 26

- ^ a b "Tomb of Philippe Pot, Grand Seneschal of Burgundy". Louvre. Retrieved 26 December 2022

- ^ "Le Tombeau de Philippe Pot". Ediciones El Viso. Retrieved 27 December 2022

- ^ a b "Début de la restauration du tombeau de Philippe Pot". Louvre, 15 May 2018. Retrieved 14 April 2019

- ^ Sadler (2015), p. 23

- ^ Jugie (2010), p. 34

- ^ "Matthew Day Jackson", 2010. Peter Blum Gallery. Retrieved 27 December 2022

- ^ Spears, Dorothy. "Matthew Day Jackson: Artist as Stuntman". HuffPost, 18 October 2010. Retrieved 27 December 2022

Sources

- Antoine, Elisabeth. Art from the Court of Burgundy: The Patronage of Philip the Bold and John the Fearless, 1364–1419. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, 2005. ISBN 978-2-7118-4864-5

- Chabeuf, Henri. Jean de La Huerta, Antoine Le Moiturier et le tombeau de Jean sans Peur, Dijon. Darantière, 1891

- De Winter, Patrick M. "Art from the Duchy of Burgundy". The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art, vol. 74, no. 10, 1987. 406–449. JSTOR 25160010

- Hofstatter, Hans. Art of the Middle Ages. Harry N. Abrams, 1968

- Hourihane, Colum. The Grove Encyclopedia of Medieval Art and Architecture, Volume 1. Oxford University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0-1953-9536-5

- Jugie, Sophie. Le Tombeau de Philippe Pot. Paris: Ediciones El Viso, 2019. ISBN 978-8-4948-2447-0

- Jugie, Sophie. The Mourners: Tomb Sculpture from the Court of Burgundy. Paris: 1; First Edition, 2010. ISBN 978-0-3001-5517-4

- Marcoux, Robert. Le tombeau de Philippe Pot: analyse et interprétation. Montréal: Université de Montréal, 2003

- McGee Morganstern, Anne. Gothic Tombs of Kinship in France, the Low Countries, and England. University Park, PA: Penn State Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-2710-1859-1

- Mikolic, Amanda. "Fashionable Mourners: Bronze Statuettes from the Rijksmuseum". Cleveland Museum of Art, 2021

- Moffitt, John. "Sluter's 'Pleurants' and Timanthes' 'Tristitia Velata': Evolution of, and Sources for a Humanist Topos of Mourning". Artibus et Historiae, vol. 26, no. 51, 2005. JSTOR 1483776

- Nash, Susie. Northern Renaissance art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-1928-4269-5

- Panofsky, Irvin; Panofsky, Gerda. "The Tomb in Arcady at the Fin-de-Siècle". Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch, volume 30, 1968. JSTOR 24655959

- Panofsky, Irvin. Tomb Sculpture. London: Harry Abrams, 1964. ISBN 978-0-8109-3870-0

- Sadler, Donna. Stone, Flesh, Spirit: The Entombment of Christ in Late Medieval Burgundy. Boston MA: Brill Academic, 2015. ISBN 978-9-0042-9314-4

- Sterling, Charles; Salinger, Margaretta. French Paintings: A Catalogue of the Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1966

External links

- Louvre catalog entry

- 19th century photograph, unidentified artist, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

![Entombment, attributed to Antoine Le Moiturier, 1490. Notre-Dame Collegiate Church of Semur-en-Auxois.[26]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/97/Semur-en-Auxois-Mise-au-tombeau-de-la-chapelle-Saint-Lazare-coll%C3%A9giale-dpt-Cote-d%27Or-DSC_0318_%28cropped%29.jpg/180px-Semur-en-Auxois-Mise-au-tombeau-de-la-chapelle-Saint-Lazare-coll%C3%A9giale-dpt-Cote-d%27Or-DSC_0318_%28cropped%29.jpg)