Developing a customized approach for strengthening tuberculosis laboratory quality management systems toward accreditation

| Full article title | Developing a customized approach for strengthening tuberculosis laboratory quality management systems toward accreditation |

|---|---|

| Journal | African Journal of Laboratory Medicine |

| Author(s) | Albert, Heidi; Trollip, Andre; Erni, Donatelle; Kao, Kekeletso |

| Author affiliation(s) | Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics |

| Primary contact | Email: heidi dot albert at finddx dot org |

| Year published | 2017 |

| Volume and issue | 6 (2) |

| Page(s) | a576 |

| DOI | 10.4102/ajlm.v6i2.576 |

| ISSN | 2225-2010 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic |

| Website | http://www.ajlmonline.org/index.php/ajlm/article/view/576/826 |

| Download | http://www.ajlmonline.org/index.php/ajlm/article/viewFile/576/816 (PDF) |

Abstract

Background: Quality-assured tuberculosis laboratory services are critical to achieve global and national goals for tuberculosis prevention and care. Implementation of a quality management system (QMS) in laboratories leads to improved quality of diagnostic tests and better patient care. The Strengthening Laboratory Management Toward Accreditation (SLMTA) program has led to measurable improvements in the QMS of clinical laboratories. However, progress in tuberculosis laboratories has been slower, which may be attributed to the need for a structured tuberculosis-specific approach to implementing QMS. We describe the development and early implementation of the Strengthening Tuberculosis Laboratory Management Toward Accreditation (TB SLMTA) program.

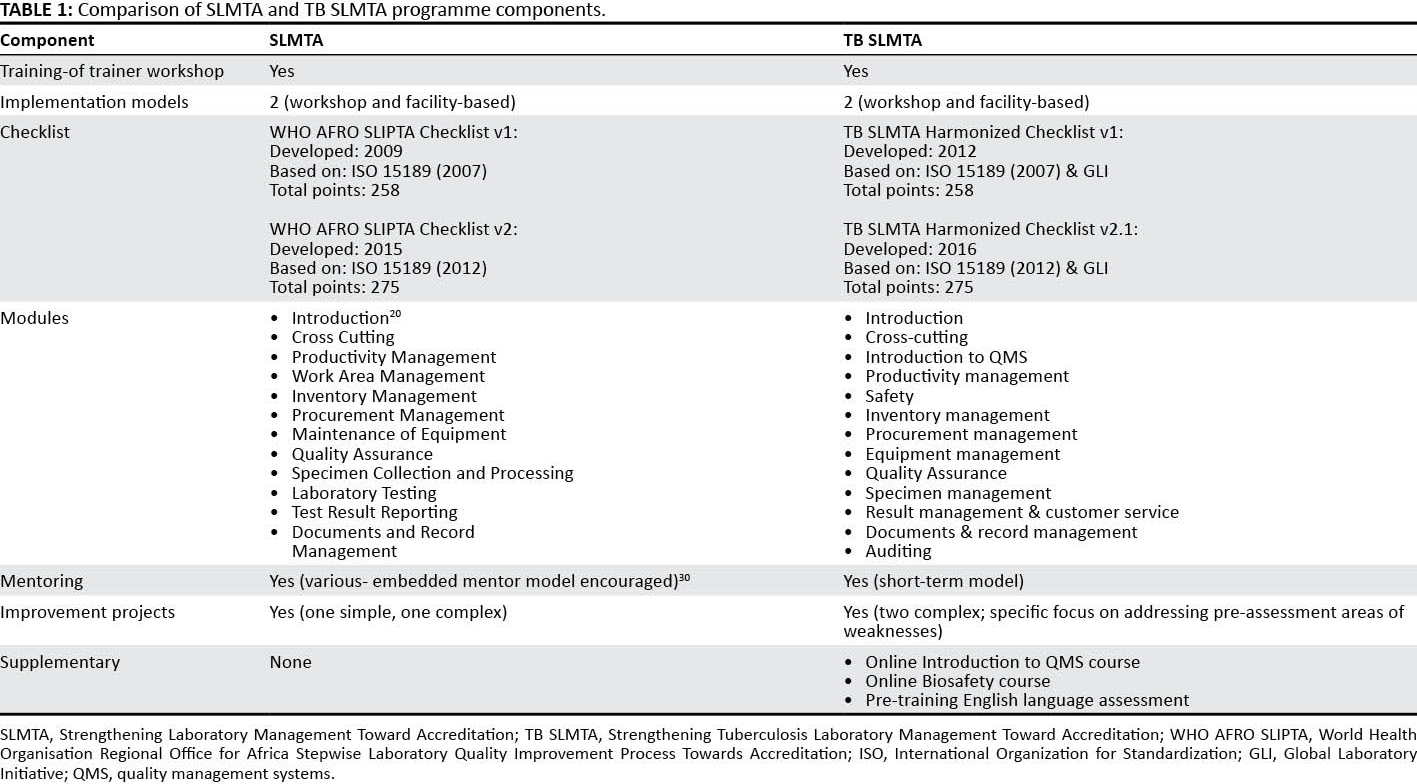

Development: The TB SLMTA curriculum was developed by customizing the SLMTA curriculum to include specific tools, job aids, and supplementary materials specific to the tuberculosis laboratory. The TB SLMTA Harmonized Checklist was developed from the World Health Organisation Regional Office for Africa Stepwise Laboratory Quality Improvement Process Towards Accreditation checklist and incorporated tuberculosis-specific requirements from the Global Laboratory Initiative Stepwise Process Towards Tuberculosis Laboratory Accreditation online tool.

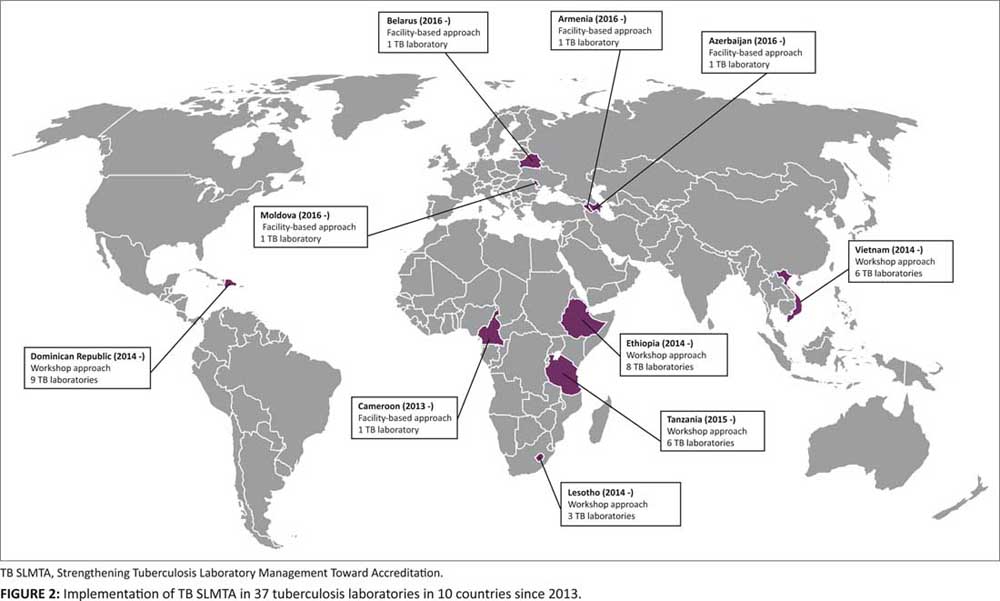

Implementation: Four regional training-of-trainers workshops have been conducted since 2013. The TB SLMTA program has been rolled out in 37 tuberculosis laboratories in 10 countries, using the workshop approach in 32 laboratories in five countries and the facility-based approach in five tuberculosis laboratories in five countries.

Conclusion: Lessons learned from early implementation of TB SLMTA suggest that a structured training and mentoring program can build a foundation towards further quality improvement in tuberculosis laboratories. Structured mentoring, and institutionalization of QMS into country programs, is needed to support tuberculosis laboratories to achieve accreditation.

Introduction

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) End TB Strategy calls for an end to the global tuberculosis epidemic. It aims to reduce deaths by 95 percent and new tuberculosis cases by 90 percent, and also ensure that no family is burdened with catastrophic expenses due to tuberculosis by 2025.[1] Despite the fall in global tuberculosis mortality by 47 percent since 1990, the disease still claimed more than 1.5 million lives in 2014.[2] A cascade of events — including poor screening, failure to link screened patients to diagnostic services, and failure to link diagnosed patients to treatment — means that many people die from tuberculosis due to delayed diagnosis and treatment initiation.[3]

Quality-assured laboratory services are critical for the provision of timely, accurate, and reliable results to support diagnosis, drug-resistance testing, treatment monitoring, and surveillance of disease. Weak laboratory systems result in high levels of laboratory error that impact patient care and undermine the confidence healthcare providers have in laboratory services.[4] In recent years, the focus on improving laboratory quality management systems (QMS), and assuring the quality of laboratory services by working toward national or international laboratory accreditation, has intensified.[5] Accreditation is the formal recognition of implementation of a QMS that adheres to international standards and has been shown to improve the quality of healthcare for patients through reduction in testing errors.[6]

The Strengthening Laboratory Management Toward Accreditation (SLMTA) program was developed by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in collaboration with the American Society for Clinical Pathology, the Clinton Health Access Initiative, and the WHO Regional Office for Africa to promote immediate and measurable quality improvement in laboratories in developing countries. SLMTA is a program that may be used to prepare laboratories for accreditation.[7] Since its launch in Kigali, Rwanda in 2009, SLMTA has been implemented in 47 countries (23 in Africa), with 617 laboratories already enrolled. Eighteen per cent of the enrolled laboratories are at the national level and most (98%) are providing HIV-related services.[8] Only four National Tuberculosis Reference Laboratories (NTRLs) in Africa have achieved international accreditation to date[9][10], and only six NTRLs have undergone a formal Stepwise Laboratory Quality Improvement Process Towards Accreditation (SLIPTA) audit by the African Society for Laboratory Medicine (T. Mekonen, personal communication). Accredited NTRLs are better equipped to support the national tuberculosis laboratory network and also provide reliable support to their national tuberculosis control and treatment programs.[11]

Since 2007, the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND) has worked with Ministries of Health to introduce new diagnostic technologies to improve the diagnosis of tuberculosis, detection of drug resistance[12] and upgrading of facilities.[13][14][15][16] Although technical capacity to conduct new tests can be developed within a relatively short time frame, persistent challenges to providing quality results in a consistent manner often remain, many of which are linked to laboratory quality system weaknesses. In 2011, through funding from the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, FIND was involved in implementation of the SLMTA program in clinical laboratories in the Dominican Republic. Measurable improvement was observed in cohorts of laboratories participating in the program. However, tuberculosis laboratories were not included in this program. Concurrently, the Global Laboratory Initiative (GLI) was developing its Stepwise Process Towards Tuberculosis Laboratory Accreditation online tool.[17] This tool provided online resources and a framework consisting of four phases, but it did not have training materials or an implementation plan to enable adoption by tuberculosis laboratories. Tuberculosis laboratories, particularly at the central or regional-level, have separate facilities from other clinical laboratories. They have different requirements for biosafety and quality assurance, and they have often been excluded from accreditation efforts. Recognizing the unique needs of tuberculosis laboratories, FIND developed a comprehensive approach to tuberculosis laboratory strengthening based on the existing SLMTA approach and incorporating aspects of the GLI Stepwise Process Towards Tuberculosis Laboratory Accreditation online tool.

In this article, we describe the development of the Tuberculosis Strengthening Laboratory Management Toward Accreditation (TB SLMTA) program and the challenges experienced during early implementation in 10 countries. We also reflect on approaches that will ensure continued quality improvement to reach accreditation and institutionalization of the program.

TB SLMTA development

Customization of training materials

In 2012, FIND conducted a review of the SLMTA materials and customized the content for tuberculosis laboratories based on available tuberculosis resources (either developed internally by FIND or by other organizations). This customization included the development of specific tools, job aids, and supplementary materials for the implementation of a QMS in the tuberculosis laboratory (Table 1), but it kept the overall structure of the SLMTA curriculum. Customization included major changes to the content of the SLMTA Facilities and Safety and Quality Assurance modules (the focus was changed from the quantitative testing in SLMTA to the qualitative and semi-quantitative testing relevant to the tuberculosis laboratory). The SLMTA Laboratory Testing and Test Result Reporting modules were combined and an Auditing module was introduced. Tuberculosis laboratory-specific tools, examples and scenarios were introduced throughout all modules in the training. The TB SLMTA Harmonized Checklist was also introduced as part of the program.

The TB SLMTA curriculum was piloted in Cape Town in April 2013 in a shortened Training-of-Trainers (TOT) Workshop led by SLMTA Master Trainers and with experienced tuberculosis laboratory specialists as participants. Following the pilot workshop, some changes were made to the training materials (e.g., organization and cross-referencing of tools, adjustment of training notes for clarity, and editing errors) and the TB SLMTA Harmonised Checklist was revised.

Subsequent review and revision of the TB SLMTA curriculum has been conducted to keep the content current with an updated GLI tool (version 2.0, 2013) and WHO Regional Office for Africa SLIPTA (2015) tool. A review of the TB SLMTA curriculum was conducted in 2015 due to experience that improvement projects did not necessarily target the highest priority non-conformities. Based on feedback from previous training, minor changes were also made to the Cross-cutting, Facilities and Safety, and Quality Assurance modules.

|

TB SLMTA Harmonized Checklist

The TB SLMTA Harmonized Checklist[18] is based on the WHO Regional Office for Africa SLIPTA checklist (2007)[19], and incorporates tuberculosis laboratory-specific requirements as provided in the GLI Stepwise Process Towards Tuberculosis Laboratory Accreditation tool, which were inserted as sub-clauses in the SLIPTA checklist. The TB SLMTA Harmonized Checklist is used to assess the QMS of the tuberculosis laboratory prior to enrollment in the program (baseline assessment) and after program completion (exit assessment). The differences between the scores obtained overall, and for each section, are a measure of the impact of the program. Assessors evaluate the laboratory operations as per checklist items, scoring the assessment and documenting their findings in detail.

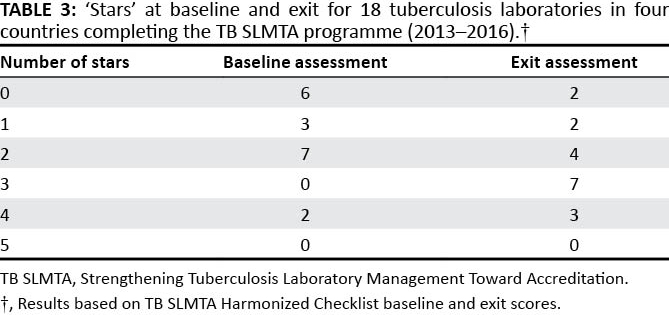

The pilot version of the TB SLMTA Harmonized Checklist[20] had additional scores allocated to the tuberculosis-specific clauses. A revised checklist (TB SLMTA Harmonized Checklist v1.0), which maintained the original SLIPTA scoring system[21], was used in the TB SLMTA roll-out. Recognition is given using a five-star grading system, with the following scores corresponding to the indicated number of stars: zero stars (0–142 points; < 55%), one star (143–165 points; 55–64%), two stars (166–191 points; 65%–74%), three stars (192–217 points; 75%–84%), four stars (218–243 points; 85%–94%) and five stars (244–258 points; ≥ 95%).

The TB SLMTA Harmonized Checklist 1.0 was recently revised in keeping with SLIPTA v2:2015, and the additional clauses of International Organization for Standardization 15189:2012. The questions added pertain to risk assessment, laboratory information systems, contingency planning, and safety. The TB SLMTA Harmonized Checklist v1.0 is available in English and Spanish. The TB SLMTA Harmonized Checklist v2.1 is available in English and Russian.[16]

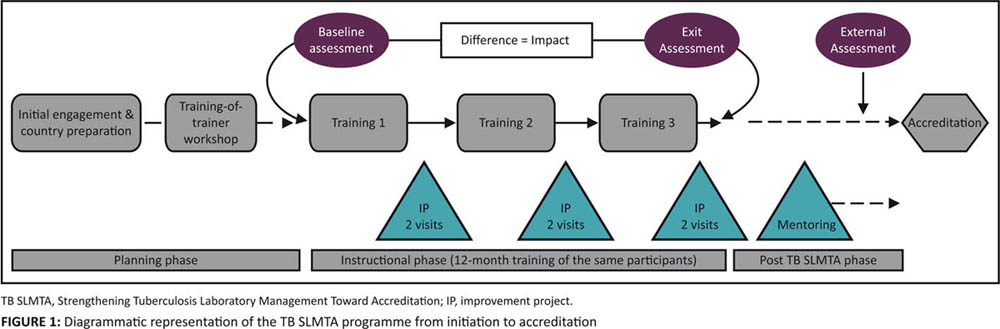

Implementation of TB SLMTA

Implementation of the TB SLMTA program starts with the initial engagement with the Ministry of Health on the program scope and expected outputs, as well as commitments required from the country (Figure 1). During this planning phase, the country selects the participating tuberculosis laboratories, the model of implementation, the trainees to attend the TOT, and the TB SLMTA participants who will attend the in-country training. Countries selects two or three participants per laboratory to attend the in-country TB SLMTA training. Typically, participants include the laboratory manager, quality officer, and one technician. After graduation from the TOT, the certified trainers implement the program in the country. Baseline and exit assessments are conducted with the TB SLMTA Harmonized Checklist v1.0 by trainers or SLIPTA-trained assessors with tuberculosis laboratory experience. In-country national or regional training is conducted over a period of 12–15 months. Between training sessions, participants work on improvement projects supervised by the TB SLMTA mentors. Post-TB SLMTA activities are conducted in the laboratories under supervision of the mentors before an external assessment determines the readiness for accreditation.

|

Training-of-trainers workshop

The TB SLMTA TOTs are conducted by SLMTA Master Trainers and are based on teach-back methodology.[22] This practice-based training approach requires trainees to play the roles of both trainer and participant as they teach the curriculum at the same time as they are learning the content. The TOTs provide trainees with an introduction to the TB SLMTA materials, practice in delivering the content and receiving feedback on their performance. The ratio of trainees to Master Trainers is a maximum of eight to one. To certify as trainers, trainees must demonstrate knowledge of TB SLMTA curriculum and proficiency in delivering training. Trainees that find teach-back challenging and do not show a good understanding of the materials graduate as one-one coaches. They can facilitate rollout in their laboratory but are not certified to train others.

Mentors are trainers who support the in-country training participants during the implementation phases between training sessions. During mentoring visits to the laboratory, they supervise the participants as they implement the improvement projects and provide resources (e.g., standard operating procedures) to implement what was taught in the training in the tuberculosis laboratory. The fundamentals of mentoring are modeled during the TOT. Trainees who are certified as trainers and who show an aptitude for mentoring are selected by the Master Trainers to perform mentoring in their countries. Mentoring in TB SLMTA builds on the relationship established between trainer and participant, and seeks to support program implementation in the laboratory. Master trainers support the certified trainers and mentors during their first national or regional training and where possible provide at least one interim visit to support mentoring. Trainers under supervision receive additional support from the Master Trainers during the workshop and, if assessed as proficient, can then graduate as trainers.

The TOTs are intensive and highly interactive, hence good language skills and a working knowledge of QMS concepts is required. Based on this observation and challenges experienced in conducting a TOT with participants with varying levels of English fluency, a mandatory online training was introduced prior to the TOT, based on the WHO's Laboratory Quality Management System: Handbook[23], to ensure that trainees have a basic understanding of QMS principles. In addition, trainees whose first language is not English are required to successfully complete an online language competency training before registration for the TOT.

Models for implementation

Two models have been adopted for implementation of TB SLMTA:

- Workshop approach: Where several tuberculosis laboratories are available in-country, or in cases where more than one country conducts centralized training, the three-workshop approach can be used. Three five-day regional workshops are conducted by trainers, approximately three months apart.

- Facility-based approach: Where there is only one tuberculosis laboratory in the country being enrolled in TB SLMTA, the facility-based approach may be used. The facility-based approach follows the same TB SLMTA curriculum, with training sessions split into three blocks over 12 months.

Factors affecting choice of implementation model include funding, number of laboratories participating in TB SLMTA, and availability of staff. TB SLMTA is targeted for implementation in tuberculosis laboratories at the national or referral level. These laboratories are conducting advanced tuberculosis testing and generally have separate facilities from general laboratories. Laboratories conducting tuberculosis testing on lower levels of the healthcare system are not targeted with this training session. However, this does not preclude the use of TB SLMTA resources to guide them, especially those related to safety and quality assurance.

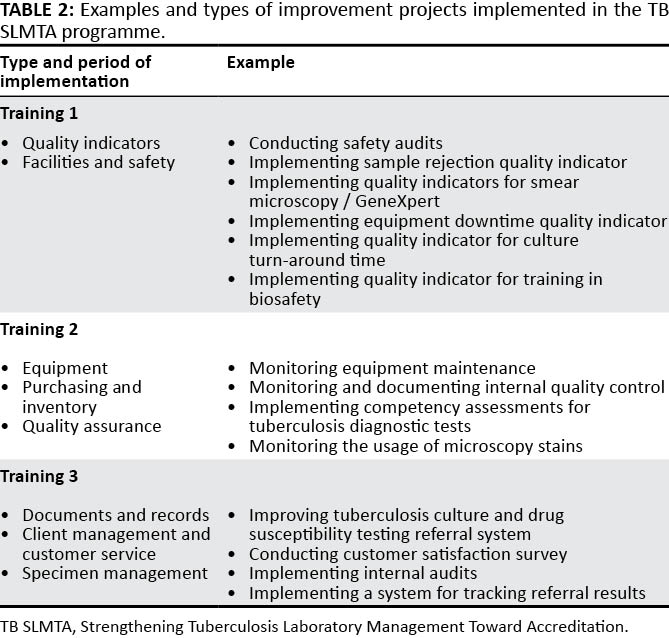

Improvement projects and mentoring

Improvement projects are broad-based activities that address weaknesses in the QMS. Topics for improvement projects are chosen from subjects covered in training. As with SLMTA (Table 1), each participant is required to complete two improvement projects between training sessions. The "just do it" project (e.g., maintaining personnel files) is implemented as a group by all the participants from the laboratory. The "complex" project, which requires extensive planning and before-and-after data collection, is chosen with assistance from the certified trainers. Ideally, laboratory management is included in the decision of the topic and scope (if laboratory managers are not participants) to ensure management engagement and allocation of time and resources to complete the projects. The projects are implemented by the participants but should involve the entire laboratory staff. Participants present their findings at national or regional workshops or on a day set aside by the laboratory (facility-based approach).

FIND found that often the choice of improvement projects does not reflect the priority gaps of the laboratory. In 2015, FIND adopted a more stringent criterion for improvement project selection. Under the guidance of certified trainers, each participant completes two improvement projects between training sessions; both are "complex" and require extensive planning and data collection. The first project is based on the subjects covered in the training. For example, Training 1 (Quality indicators and Facilities and safety), Training 2 (Equipment, Purchasing and inventory, and Quality assurance) and Training 3 (Documents and records, Client Management and Customer Service, and Specimen management) (Table 2). The second project addresses the weaknesses identified during the baseline assessment. These non-conformities are split between the participants, and a different section of the TB SLMTA Harmonized Checklist is covered between training sessions.

TB SLMTA uses a short-term mentoring model instead of the embedded model encouraged by SLMTA. Mentoring visits are conducted by the trainers over two or three days. Each facility receives two visits between each workshop. The outcomes of the mentoring visits and, in particular, the progress with improvement projects, is monitored by the mentors for each laboratory, and any necessary support is provided. Standardized data collection tools are used to record the findings of mentor visits.

|

Results from TB SLMTA implementation workshops

Since 2013, four regional TOTs have been conducted in Lesotho, Vietnam, South Africa, and Moldova. Seventy trainees from 27 counties have been trained, and 59 are certified as trainers (including trainers under supervision), of which four participants are from WHO Supranational Reference Laboratories that provide tuberculosis laboratory technical support to countries. Twenty-six trainers are currently active in the TB SLMTA program. Currently there are three Master Trainers. One Master Trainer, based in the African region, graduated after conducting a round of TB SLMTA, and we expect two more graduates in the coming year (one in the African region and one in South East Asia) for a total of six Master Trainers.

The TB SLMTA program has been rolled out in 37 tuberculosis laboratories in 10 countries (Figure 2). National or regional TB SLMTA training using the workshop approach were conducted in 32 laboratories in five countries (Dominican Republic, Ethiopia, Lesotho, Tanzania, and Vietnam). The facility-based approach has been used in one regional tuberculosis laboratory in Cameroon. The instructional phase is complete in these laboratories but is ongoing in the four NTRLs in Eastern Europe (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, and Moldova).

|

Baseline and exit assessment scores for 18 laboratories in four countries (Cameroon, Ethiopia, Lesotho, and Tanzania) were available for analysis and are summarized in Table 3. At baseline, six of the 18 laboratories had a zero-star rating, three had a one-star rating, seven had a two-star rating and two laboratories had a four-star rating. No laboratories had three- or five-star ratings at baseline assessment. At exit, two laboratories remained at zero stars, two were rated at one-star, four laboratories were rated at two stars, seven were rated at three-stars and three laboratories were rated at four-stars. The impact of TB SLMTA, as well as the individual country experiences will be addressed in separate publications.

|

FIND developed an online biosafety training program in 2014[24], and TB SLMTA participants in Tanzania and Lesotho were enrolled in this training to complement the basic biosafety module of the TB SLMTA programme. This task-based online training was implemented in conjunction with biosafety improvements projects following Workshop 1.

Active participation for this extended time of the in-country training is a challenge for trainers and participants alike. In our cohort, 21 participants (Lesotho, one; Dominican Republic, eight; Ethiopia, seven; Tanzania, three; Vietnam, two) were unable to complete the compulsory training and improvement projects due to personal or job-related reasons. Although in most cases additional participants from the same laboratory meant that the laboratory was not excluded from continuing the program, one regional tuberculosis laboratory in Tanzania was not able to complete the program as both participants were unable to finish the training.

Discussion

Tuberculosis laboratories are an essential element of tuberculosis prevention and care, providing testing for diagnosis, surveillance, and treatment monitoring that can be accessible at all levels of the healthcare system. The TB SLMTA program provides tuberculosis laboratories with customized support to accelerate the process of strengthening their QMS towards accreditation. There is an urgent need to expand the program, as only 21 NTRLs (43%) on the African continent have received SLMTA training, and only four NTRLs have reached accreditation. Although 44% of NTRLs report implementing a QMS, the extent of implementation is not known.[25]

There were a number of challenges to implementing the TB SLMTA program in the initial cohort of laboratories. The lack of experienced assessors was a challenge in some countries. SLIPTA-trained assessors with experience in tuberculosis testing were used to supplement certified TB SLMTA trainers. However, limited hands-on time spent with the TB SLMTA Harmonized Checklist during the TB SLMTA TOT, and SLIPTA trained assessors who are unfamiliar with implementing the tuberculosis laboratory specific clauses, may lead to inflated scoring during these assessments. While laboratories enrolled in the TB SLMTA program may use the WHO Regional Office for Africa SLIPTA checklist, the additional components from GLI included in the TB SLMTA Harmonized Checklist v1.0 enable technical assessment alongside assessment of International Organization for Standardization (ISO) components.

In instances where management had not been fully engaged in the TB SLMTA implementation, participants struggled to complete the improvement projects. It is therefore critical to actively engage upper management, both at the facility level and at the national Ministry of Health, to ensure their commitment to the program. Institutionalization of the QMS into country programs will be needed to support tuberculosis laboratories in achieving accreditation. Training and quality improvement activities may be seen as extra workload, especially in settings where staff shortages and high workload are existing challenges. Furthermore, trainers and mentors, who were critical components of the program, are required to support the program in addition to their usual duties. This may put additional strain on the laboratory, as other staff are required to cover their workstations during their absence.

In addition to senior-level engagement of the Ministry of Health, QMS activities being conducted by various implementing partners and donors should be coordinated centrally to ensure synergy to avoid duplication of effort and the risk of confusion and wastage of resources. We found multiple partners conducting overlapping activities related to QMS without clear coordination to ensure cost-efficiency and maximum impact from available resources. Partners should seek active collaboration on QMS activities, harmonization of approaches, and contributions of various groups, under the leadership and coordination of the Ministry of Health.

The TOTs are highly interactive, and some trainees whose first language is not English find the training challenging. Introduction of language proficiency and an introduction to QMS online training in 2014 helped ensure that trainees in the TOTs were successfully certified as trainers. However, this approach limits potential trainees. In 2016, FIND conducted a TOT in English, with real-time Russian translation (using a tuberculosis laboratory specialist as translator). All the trainees passed, suggesting that the model can be expanded to non-English speaking countries using translated materials (including the TB SLMTA Harmonized Checklist) and real-time translation. Careful considerations must be given to the translator, with preference given to those who have an insight into laboratory testing or QMS. Further analysis of this approach is required. Master Trainers are certified after successful supervision of the roll-out of the TB SLMTA program in a country. To facilitate the expansion of the TB SLMTA program, there is a need for more Master Trainers, particularly those that can train in languages other than English.

As noted earlier, FIND recently adopted a more stringent criterion for improvement project selection. A focus on the weaknesses identified in baseline assessment, in particular quality indicator and quality control monitoring and safety in the tuberculosis laboratory, has the potential to improve the impact of the TB SLMTA program. As the cohort of tuberculosis laboratories that have used this strategy increases, the impact will be measured.

Mentoring of laboratories was found to be an important component to successful implementation of SLMTA. Embedded mentoring has proven to result in measurable improvement in the QMS in many countries, including Lesotho, Zimbabwe, Kenya, and Nigeria.[26][27][28][29] In TB SLMTA, certified trainers mentor participants during site visits and remotely between workshops. This short-term mentoring model is cost-effective, scalable, and sustainable, and it is well suited to the workshop approach of implementation used in our cohort. Ongoing structured mentoring of the tuberculosis laboratories that obtained four-star ratings at TB SLMTA exit assessment is being conducted in preparation for accreditation. The TB SLMTA program is currently focused on tuberculosis laboratories with the capacity to perform advanced diagnostics such as culture and drug susceptibility testing. Tuberculosis laboratories on the lower level of the healthcare system may consider integration into current SLMTA activities. In addition, if feasible, countries should consider sharing mentoring and assessments between programs. These cost-cutting approaches have an added benefit of integrating services and present opportunities for knowledge sharing and will encourage sustainability and institutionalization of the QMS.

Limitations

This study is subject to a number of limitations. Firstly, none of the TB SLMTA laboratories have reached accreditation yet, and we are thus reporting on intermediate measures of quality improvement leading to the ultimate target of accreditation. Second, quality improvement from three stars to five stars (which is considered equivalent to accreditation readiness) is challenging.[30] Third, the role of mentors in this final phase is still to be determined. Finally, in this article we have not addressed the costs of TB SLMTA. A cost estimation exercise is being undertaken. We do not expect the costs to differ substantially from costs of the SLMTA program as reported by others.[31]

Conclusions

TB SLMTA is a structured training and mentoring program that is customized to meet the needs of tuberculosis laboratories implementing a QMS in resource-limited settings within a reasonably short time frame, building a foundation toward further quality improvement toward achieving accreditation. Expansion of this program is an urgent priority to address the need for accreditation of tuberculosis laboratories on the African continent and beyond.

Acknowledgements

The findings and conclusions in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Sources of support

We are grateful to the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief through the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (3U2GPS002746), ExpandTB, UNITAID, UK Aid, Aus Aid, and the WHO for funding support.

Authors’ contributions

H.A., A.T. and K.K. contributed to development and implementation of the program, data analysis, and preparation and critical review of the manuscript. D.E. contributed to the data analysis. All authors agreed with the content of the manuscript.

References

- ↑ World Health Organization (2015). "WHO End TB Strategy: Global strategy and targets for tuberculosis prevention, care and control after 2015". http://who.int/tb/post2015_strategy/en/. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2015). "Global Tuberculosis Report 2015" (PDF). ISBN 9789241565059. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/191102/1/9789241565059_eng.pdf. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ↑ Kuznetsov, V.N.; Grjibovski, A.M.; Mariandyshev, A.O. et al. (2014). "Two vicious circles contributing to a diagnostic delay for tuberculosis patients in Arkhangelsk". Emerging Health Threats Journal 7: 24909. doi:10.3402/ehtj.v7.24909. PMC PMC4147085. PMID 25163673. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4147085.

- ↑ Alemnji, G.A.; Zeh, C.; Yao, K.; Fonjungo, P.N. (2014). "Strengthening national health laboratories in sub-Saharan Africa: a decade of remarkable progress". Tropical Medicine & International Health 19 (4): 450-8. doi:10.1111/tmi.12269. PMC PMC4826025. PMID 24506521. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4826025.

- ↑ Gershy-Damet, G.M.; Rotz, P.; Cross, D. et al. (2010). "The World Health Organization African region laboratory accreditation process: Improving the quality of laboratory systems in the African region". American Journal of Clinical Pathology 134 (3): 393-400. doi:10.1309/AJCPTUUC2V1WJQBM. PMID 20716795.

- ↑ Peter, T.F.; Rotz, P.D.; Blair, D.H. et al. (2010). "Impact of laboratory accreditation on patient care and the health system". American Journal of Clinical Pathology 134 (4): 550-5. doi:10.1309/AJCPH1SKQ1HNWGHF. PMID 20855635.

- ↑ Yao, K.; McKinney, B.; Murphy, A. et al. (2010). "Improving quality management systems of laboratories in developing countries: An innovative training approach to accelerate laboratory accreditation". American Journal of Clinical Pathology 134 (3): 401–9. doi:10.1309/AJCPNBBL53FWUIQJ. PMID 20716796.

- ↑ Yao, K.; Luman, E.T.; SLMTA Collaborating Authors (2014). "Evidence from 617 laboratories in 47 countries for SLMTA-driven improvement in quality management systems". African Journal of Laboratory Medicine 3 (3): 262. doi:10.4102/ajlm.v3i2.262. PMC PMC4706175. PMID 26753132. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4706175.

- ↑ "Directory of Accredited Facilities". South African National Accreditation System. 2015. http://home.sanas.co.za/?page_id=38. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ↑ "Directório de Entidades Acreditradas". Instituto Português de Acreditação. http://www.ipac.pt/pesquisa/acredita.asp. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ↑ Ridderhof, J.C.; van Deun, A.; Kam, K.M. et al. (2007). "Roles of laboratories and laboratory systems in effective tuberculosis programmes". Bulletin of the World Health Organization 85 (5): 354-9. PMC PMC2636656. PMID 17639219. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2636656.

- ↑ Raizada, N.; Sachdeva, K.S.; Chauhan, D.S. et al. (2014). "A multi-site validation in India of the line probe assay for the rapid diagnosis of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis directly from sputum specimens". PLoS One 9 (2): e88626. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088626. PMC PMC3929364. PMID 24586360. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3929364.

- ↑ Raizada, N.; Sachdeva, K.S.; Sreenivas, A. et al. (2014). "Feasibility of decentralised deployment of Xpert MTB/RIF test at lower level of health system in India". PLoS One 9 (2): e89301. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0089301. PMC PMC3935858. PMID 24586675. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3935858.

- ↑ Albert, H.; Bwanga, F.; Mukkada, S. et al. (2010). "Rapid screening of MDR-TB using molecular Line Probe Assay is feasible in Uganda". BMC Infectious Diseases 10: 41. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-10-41. PMC PMC2841659. PMID 20187922. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2841659.

- ↑ Albert, H.; Manabe, Y.; Lukyamuzi, G. et al. (2010). "Performance of three LED-based fluorescence microscopy systems for detection of tuberculosis in Uganda". PLoS One 5 (12): e15206. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015206. PMC PMC3011008. PMID 21203398. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3011008.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Paramasivan, C.N.; Lee, E.; Kao, K. et al. (2010). "Experience establishing tuberculosis laboratory capacity in a developing country setting". International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 13 (1): 59-64. PMID 20003696.

- ↑ "GLI Stepwise Process towards TB Laboratory Accreditation". Global Laboratory Initiative. http://www.gliquality.org/. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ↑ "TB Laboratory Quality Management Systems Towards Accreditation Harmonized Checklist" (PDF). FIND. February 2016. https://www.finddx.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/NEW-TB-Harmonized-Checklist-v2.1-2-2016.pdf. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ↑ "WHO AFRO SLIPTA Checklist". African Society for Laboratory Medicine. 2007. http://www.afro.who.int/en/downloads/cat_view/1501-english/787-blood-safety.html. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ↑ Maruta, T.; Albert, H.; Hove, P. et al. (2012). "Harmonizing quality improvement of TB laboratories with generic accreditation initiatives". ASLM Conference Proceedings. http://citeweb.info/20121448643.

- ↑ Albert, H. (2014). "Strengthening laboratory management toward accreditation programme: Transforming the lab landscape in developing countries and customisation for labs". Proceedings of the 45th Union World Conference on Lung Health. http://html5.slideonline.eu/event/14UNION.

- ↑ Maruta, T.; Yao, K.; Ndlovu, N. et al. (2014). "Training-of-trainers: A strategy to build country capacity for SLMTA expansion and sustainability". African Journal of Laboratory Medicine 3 (2): 196. doi:10.4102/ajlm.v3i2.196. PMC PMC4703333. PMID 26753131. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4703333.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2011). "Laboratory Quality Management System: Handbook". ISBN 9789241548274. http://www.who.int/ihr/publications/lqms/en/. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ↑ Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics. "FIND Online Training". http://finddiagnostics-training.org/moodle/. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ↑ Albert, H.; de Dieu Iragena, J.; Kao, K. et al. (2017). "Implementation of quality management systems and progress towards accreditation of National Tuberculosis Reference Laboratories in Africa". African Journal of Laboratory Medicine 6 (2): 490. doi:10.4102/ajlm.v6i2.490. PMC PMC5523922. PMID 28879161. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5523922.

- ↑ Maruta, T.; Motenbang, D.; Mathabo, L. et al. (2012). "Impact of mentorship on WHO-AFRO Strengthening Laboratory Quality Improvement Process Towards Accreditation (SLIPTA)". African Journal of Laboratory Medicine 1 (1): 6. doi:10.4102/ajlm.v1i1.6. PMC PMC5644515. PMID 29062726. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5644515.

- ↑ Nzombe, P.; Luman, E.T.; Shumba, E. et al. (2014). "Maximising mentorship: Variations in laboratory mentorship models implemented in Zimbabwe". African Journal of Laboratory Medicine 3 (2): 241. doi:10.4102/ajlm.v3i2.241. PMC PMC5637805. PMID 29043196. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5637805.

- ↑ Makokha, E.P.; Mwalili, S.; Basiye, F.L. et al. (2014). "Using standard and institutional mentorship models to implement SLMTA in Kenya". African Journal of Laboratory Medicine 3 (2): 220. doi:10.4102/ajlm.v3i2.220. PMC PMC5637804. PMID 29043191. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5637804.

- ↑ Maruta, T.; Rotz, P.; Peter, T. et al. (2013). "Setting up a structured laboratory mentoring programme". African Journal of Laboratory Medicine 2 (1): 77. doi:10.4102/ajlm.v2i1.77. PMC PMC5637775. PMID 29043168. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5637775.

- ↑ Ndihokubwayo, J.B.; Maruta, T.; Ndlovu, N. et al. (2016). "Implementation of the World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa Stepwise Laboratory Quality Improvement Process Towards Accreditation". African Journal of Laboratory Medicine 5 (1): 280. doi:10.4102/ajlm.v5i1.280. PMC PMC5436392. PMID 28879103. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5436392.

- ↑ Shumba, E.; Nzombe, P.; Mbinda, A. et al. (2014). "Weighing the costs: Implementing the SLMTA programme in Zimbabwe using internal versus external facilitators". African Journal of Laboratory Medicine 3 (2): 248. doi:10.4102/ajlm.v3i2.248. PMC PMC5637799. PMID 29043197. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5637799.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to grammar, spelling, and presentation, including the addition of PMCID and DOI when they were missing from the original reference. Reference 19 is a dead URL, and an archived version could not be located. Reference 21 can't be found at the author-supplied URL.