Informatics Educational Institutions & Programs

Contents

| Cross Temple | |

|---|---|

| Native name Chinese: 十字寺 | |

A Yuan-era stele in the ruins of the Cross Temple. Another stele (left) and some scattered groundwork (right) are visible in the background. | |

| Type | Abandoned Buddhist and Nestorian Christian religious site |

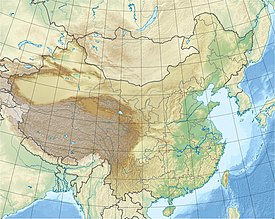

| Location | North Sanpen Mountain, Chechang Village, Zhoukoudian, Fangshan District, Beijing |

| Coordinates | 39°44′35″N 115°54′06″E / 39.74306°N 115.90167°E |

| Built | Possibly 317 |

| Rebuilt | 639, c. 960, 1365, 1535 |

The Cross Temple (Chinese: 十字寺; pinyin: Shízì sì)[a] is a former place of worship in Fangshan, Beijing. During different periods, it was used by either Buddhists or the Church of the East (sometimes known as Nestorian Christianity). It is the only site of the Church of the East in China still in existence.

Scholars debate the periodisation of when the Cross Temple was used by Nestorians. Originally built as Buddhist temple, the site was in use by Nestorians during the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368)—with some hypothesising that it had also been used by Nestorians during the Tang dynasty (618–907). After the end of the Yuan, the temple reverted to Buddhist use until its sale in the early 20th century. The site's buildings were demolished during the late 1950s; presently, only pedestals, steles, and the buildings' foundations remain on-site. In 2006, the ruins were named a Major Historical and Cultural Site Protected at the National Level.

Today, the site features two ancient steles, as well as groundwork and the bases of several pillars. During the early 20th century, two stone blocks featuring carved crosses were discovered at the site; they are now on display at the Nanjing Museum.

History

Context and terminology

During its history, the Cross Temple was used by either Chinese Buddhists or Nestorian Christians in China, formally known as the Church of the East in China. They were known as Jingjiao (景教; 'The Luminous Religion') during the Tang dynasty, and Yelikewen (也里可溫) during the Mongolian Yuan dynasty.[4]

There are some controversies on the usage of "Nestorian" to refer to the Church of the East. Certain scholars, such as Peter Hofrichter, refuse to refer to the historical Church of the East in China as "Nestorian", as the word implies a heretical connection to Nestorius, and that the theology of early Chinese Christianity does not entirely correspond to Nestorianism.[5] However, Mar Aprem, a metropolitan bishop in the Assyrian Church of the East, welcomed the use of "Nestorian", stating that "the name Nestorian Church is not without honour in the missionary history of the Church [...] Especially in China, the name of the Nestorian Church is an honourable name."[6] This article will use the terms "Nestorian" and the "Church of the East in China" interchangeably.

Christianity first came to China in 635, during the Tang dynasty, through a Nestorian mission led by Alopen, which was recorded on the Xi'an Stele.[7] According to Tang Li (唐莉), thriving China-Persia relations, religious tolerance by Emperor Taizong of Tang, and trade along the Silk Road facilitated the introduction of Christianity.[8] The missionaries built Nestorian monasteries in every province during the reign of Emperor Gaozong of Tang (650–683).[9][10] The Church of the East in China survived until 845, when Emperor Wuzong of Tang enacted the Huichang persecution of Buddhism, which also affected the Christians. Nestorian Christianity in Tang China fell into decline afterwards.[11]

Nestorian Christianity continued to exist among the Mongolian tribes in Northwestern China.[12] It reemerged in Chinese historical records during the Mongol-ruled Yuan dynasty, when it was known as "Yelikewen".[13] The Yuan imperial court established the office of Chongfu Si (崇福司; 'Administration of Honoured Blessing') to administrate Christian activities in China, which oversaw many Nestorian churches.[14] The Church of the East in China fell into decline again after the end of the Yuan dynasty, partly because Nestorians in Yuan China were mostly of the minority Semu caste.[b][15] After the Han Chinese Ming dynasty was established, many Semu people assimilated into Han culture and no longer proclaimed themselves to be Muslims or Christians, leading to the annihilation of Nestorian Christianity in China.[15]

Early history of the Cross Temple

According to a Liao-era stele at the temple site, a Buddhist monk named Huijin (惠靜) began building the temple in 317—the first year of the reign of Emperor Yuan, founder of the Eastern Jin dynasty (317–420).[16] In 639, during the Tang dynasty (618–907), a monk named Yiduan (義端) re-furnished the temple.[16] The scholar Wang Xiaojing proposed that the author of the Liao stele conflated the Jin with the Later Jin dynasty (936–947).[17] Names for the monastery during Jin and Tang periods is not known.[18]

Some scholars suggested that the temple may have belonged to the Church of the East in China around the Tang dynasty. The Japanese scholar P. Y. Saeki speculated that believers fleeing from Chang'an (modern Xi'an, the capital of the Tang Empire) to Youzhou and Liaodong[c] during the 9th-century Huichang persecution, began using the temple.[19][20] Tang Xiaofeng additionally pointed to inscriptions on the Liao stele as an indication that Christian crosses were present at the temple prior to the Liao dynasty. In addition, Tang claimed that another text written by Li Zhongxuan in 987 indicated a Nestorian presence in Youzhou.[21] However, British sinologist Arthur Christopher Moule believed that there was insufficient evidence to show that the Church of the East existed in Beijing before the 13th century.[20]

Liao dynasty: Buddhist use

The Cross Temple used to be called "Chongsheng Yuan" (崇聖院; 'Hall of the Honoured Saint') during the Liao dynasty, when Buddhists rebuilt it during the reign of Emperor Muzong of Liao. However, the exact date of rebuilding was unclear: although the stele claims the tenth year of Emperor Yuan's reign—corresponding to 960—it states "Bingzi" (丙子) as the sexagenary cycle; these two statements do not align,[22] differing by a span of 16 years.[23] The Liao stele does not indicate any relationship between the site and Christianity, and it is believed that Chongsheng Yuan was a Buddhist temple.[24] The scholar Xu Pingfang held that Nestorian activities at the site commenced only after Buddhist activity had ended.[25] Xu also believed that the errors in the stele text were not likely made by the original authors, but by Ming people who re-carved the steles.[26]

Yuan dynasty: Christian use

Nestorian Christianity spread throughout the area after the Mongol conquest of the Jurchen Jin capital of Zhongdu (near modern Beijing) in 1215. Under the Mongol-Yuan regime, Beijing had a metropolitan bishop.[27] There are several theories on how the Cross Temple, located outside of Beijing, came into Christian use during the Yuan dynasty. Wang hypothesized that a Nestorian passed by Fangshan, discovered the abandoned temple, and turned it into a monastic retreat.[28] Tang Xiaofeng and Zhang Yingying suggested it is also possible that the Cross Temple was rebuilt during this period.[29]

Many scholars have considered that the Nestorian monk Rabban Sauma, a Uyghur born in Beijing during the Yuan,[30][31] may have some connection to the Cross Temple. Moule conjectured that the site was probably near the retreat of Sauma.[32] Shi Mingpei argues that the description of Rabban Sauma's retreat is "extremely similar" to the Cross Temple and its surrounding terrain.[33] In her 2011 book East Syriac Christianity in Mongol-Yuan China, Tang Li asserted that Rabban Sauma came from the site.[34]

Wang estimated that Nestorian Christians abandoned the site before 1358, when it began to be rebuilt by Buddhist monks;[28] this rebuilding was completed in 1365.[24] According to the Yuan stele, a Buddhist monk named Jingshan (淨善) initiated the reconstruction because he dreamed of a deity in his meditation, and then saw a shining cross on top of an ancient dhvaja at the temple site.[35] The Yuan stele records the temple's major benefactors as being the prince of Huai Temür Bukha, the eunuch-official Zhao Bayan Bukha (趙伯顏不花), and the minister Qingtong, with the inscription itself being made by Huang Jin.[25] In 1992, Xu Pingfang suggested that Temür Bukha would be familiar with Nestorian practices because of his Nestorian grandmother Sorghaghtani Beki. Therefore, he would request that the Buddhist temple continue to use the name "Cross Temple" when it was rebuilt, and that its Nestorian artefacts to be preserved.[25] However, modern scholars generally consider the information regarding the Yuan benefactors to be false, and the inscription itself to be a forgery done during the Ming dynasty.[36][37]

Wang suggested that the official name of the temple during the Yuan period was "Chongsheng Yuan".[28] She further argued that the Han Chinese population at the time used the term "cross temple" to refer to Nestorian churches in general, and that Nestorians at the time would not have called it "Cross Temple".[38] However, because the name "Cross Temple" was simple and direct, local residents began to use it after the arrival of the Nestorians.[39]

Ming and Qing dynasties: Buddhist use

Nestorian Christians continued to have a presence in northern China during the early Ming dynasty (1368–1644). During the reign of Emperor Yingzong of Ming (1436–1449), some Nestorians were still present in Fangshan: a record shows that some Nestorian monks visited the Yunju Temple, which is also in Fangshan, around the year 1437.[d][25][40] The Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci (1552–1610, active in China 1582–1610) learned from a Jewish person that there was an existing Nestorian population in northern China during the early Ming. Ricci was told that the Chinese Nestorians were keeping their religious identity a secret, but they still referred to a former Nestorian church as the "Cross Church".[41]

In 1535, the site was rebuilt by a Buddhist monk named Dejing (德景), supported by local villagers and the family of Gao Rong (高榮), a nephew of the powerful Ming eunuch official Gao Feng. During reconstruction, the inscriptions of the Liao and Yuan steles were altered—with the building officially known as the "Cross Temple" by this time.[28]

During the Qing dynasty, in the History of Fangshan County (房山縣誌) compiled around 1664, the Cross Temple was briefly mentioned. It was listed along with other Buddhist temples in the county.[42] In his Yifengtang Jinshi Wenzi Mu (藝風堂金石文字目; 'Index of Texts of Bronze and Stone Inscriptions by Yifengtang') written in 1897, Miao Quansun included the text of the Liao stele.[43] Around 1911, the Buddhist monks sold the temple and the surrounding lands.[44]

Modern rediscovery and development

According to P. Y. Saeki, the Scottish diplomat Reginald Johnston rediscovered the site during the summer of 1919.[46][47] Saeki himself visited the site in 1931, and recorded that most of the site's buildings still existed at that time.[42] According to Saeki, there was a Shanmen entry. The Shanmen entry was followed by the Hall of Four Heavenly Kings. Beyond the hall, there was a courtyard with two gingko trees, and the Liao and Yuan steles were next to each tree. To the right of the courtyard, there was a kitchen and a dormitory for the monks. To the left of the courtyard, there was another dormitory building. The Main Hall of the temple was at the end of the courtyard, and it contained three statues of Buddha.[48] A 21st-century study measured that the Shanmen building was 17.5 m (57 ft) to the south of the Main Hall, with dimensions 7.08 m (23.2 ft) by 11.24 m (36.9 ft).[49]

In the 1950s, following the establishment of the People's Republic of China, the remaining buildings of the Cross Temple were destroyed.[50] During the Cultural Revolution, the two steles were knocked down and broken into pieces.[51] In the 1990s, the Beijing branches of the China Christian Council (CCC) and the Three-Self Patriotic Movement (TSPM) rebuilt the walls around the Cross Temple site.[52] In 2006, its ruins were named a Major Historical and Cultural Site Protected at the National Level.[53]

Current state

The Cross Temple is the only discovered site of the Church of the East in China.[54][e] It is located near Chechang Village (车厂村), Fangshan District, to the southwest of Beijing City. The grounds are 50 m (160 ft) across from east to west, and 45 m (148 ft) across from north to south. It is surrounded by walls on four sides, with entrances in the north and south.[56] After severe rain in 2012 damaged the site and the walls, gutters and surveillance cameras were added.[57]

No buildings remain standing at the site of the Cross Temple.[56] There is some groundwork at the north and west parts of the site, where the Main Hall and the dormitory of the Buddhist monks once stood.[58] The Main Hall site has dimensions 11.32 m (37.1 ft) from north to south, and 19.6 m (64 ft) from east to west. There are pillar bases scattered the ruins of the Main Hall, and remnants of stairs in front.[56] In front of the Main Hall, there are two gingko trees: one ancient and one new. The newer tree was planted to replace another ancient one, which was destroyed by fire.[52] There is a footpath between the trees. On the southern part of the path, there is a Yuan dynasty stele, and a Liao dynasty stele is to its east.[49] To the south of the Yuan stele, there are some hardly noticeable marks of the Shanmen building.[49]

Relics

Stone steles

There are two steles at the Cross Temple site: the Liao stele was raised in 960, and the Yuan stele was raised in 1365. Both were re-carved during the Ming dynasty in 1535. During the Cultural Revolution, the Liao stele was broken in the middle and part of its bottom left corner went missing, while the Yuan stele was broken into three pieces. During the early 21st century, both were repaired and re-raised.[51] Both steles bear inscriptions, though they do not explicitly mention Christianity.[36] The Yuan stele features a cross at its top, but according to the scholar Wang Xiaojing, it is not likely made by the Nestorians, as stele making was a Han Chinese practice, but there were very few Han Nestorians during the Yuan dynasty.[59]

Scholars generally agree that while the two steles were from the Liao and Yuan dynasties respectively, their inscriptions were tampered with by Ming writers, and there are errors in their stated dates and names of individuals.[60][61] According to Wang Xiaojing, in order to elevate the temple's status and garner more support and donations from Buddhists,[62] the Ming writers changed the inscriptions of the two steles to claim that the temple received royal charters,[63] that it had received donations from famous figures, and that it had been larger in size during the Yuan period. Tang Xiaofeng and Zhang Yingying suggest that the altered inscriptions were based on existing rumours.[61]

A replica of the Xi'an Stele was added to the site during the early 21st century, placed in front of the north wall.[49] Made in 781, the original stele features a cross on top, and records Christian doctrines, a brief history of the advent of the Church of the East in China during the Tang dynasty, a eulogy and the names of the contemporary clergy.[64] It was discovered near Xi'an in the 1620s.[65] The scholar Tang Li called it "one of the most important sources for the study of Nestorian Christianity in China."[66]

Stone plaque

A stone plaque inscribed with the characters 『古剎十字禪林』 ('Ancient Cross Buddhist Temple')[67] had previously been installed atop the temple's gate.[68] Records from 1919 indicated the plaque was still present, but in 1931 Saeki noted that it had fallen off and broken.[67][69] When Wu Mengling (吴梦麟) visited the site in October 1992, he found one of the broken pieces in front of the gingko trees.[69] According to Wang, the plaque is currently stored by the Fangshan District Bureau of Cultural Artifacts,[69] though Tang and Zhang claimed it is on display at the Beijing Stone Carving Art Museum.[70]

Carved stone blocks

There were previously two blocks of carved stone at the Cross Temple site. The two stone blocks are rectangular, with a vertical hollow in the rear. They are 68.5 cm (27.0 in) tall and 58.5 cm (23.0 in) wide. For each, the front face and sides are 22 cm (8.7 in) and 14 cm (5.5 in) thick, respectively. Each have crosses carved into their front face, and flowers carved into each of their two sides.[71] The scholar Niu Ruiji claimed that the two stone blocks were originally connected, with the two crosses at the opposite ends.[72]

The two stone blocks were first mentioned by H. I. Harding, second secretary of the English mission in Beijing,[2] who wrote that they were discovered in the summer of 1919 by Christopher Irving—a pseudonym of Reginald Johnston.[46][73] Harding recorded claims by the monks that the blocks had been discovered underground in 1357, during repairs to the temple's Hall of Heavenly Kings.[74] In 1921, Francis Crawford Burkitt published his identification and translation of the inscriptions on one of the stone blocks.[75][32]

Fearing that foreigners might remove the stone blocks from the site, Zhuang Shangyan and Wang Zuobin of the Peiping Commission for the Preservation of Antiquities (北平古物保管委員會, "Peiping" is one of the former names of Beijing) surveyed the site in September 1931.[71] The following month, the blocks were transported to the Peiping Museum of History (北平歷史博物館) for exhibition.[71][52] During the Second Sino-Japanese War, they were transferred to Nanjing, and are currently on display in the Nanjing Museum. A replica of one of the blocks is in the collection of the National Museum of China, and two replicas are at the nearby Yunju Temple.[52]

According to Tang Li, Christians following East Syrian traditions in the Far East often showed an adoration of the cross and images.[76] While both feature crosses and flowers in vases, details of the carvings differ between the two blocks. The sides of one block feature chrysanthemums in a vase;[71] the cross on its front is supported by clouds and lotuses, and features a Baoxianghua pattern at its centre. Additionally, the cross is surrounded by an inscription in Syriac, which reads:[71][32]

ܚܘܪܘ ܠܘܬܗ ܘ ܣܒܪܘ ܒܗ[f]

Look ye unto it and hope in it.

— Psalms 34:5-6 (Peshitta version)[78]

According to P. G. Borbone, the text is often associated with the triumphal cross. The text-cross combination is also found on a funerary inscription near Chifeng, Inner Mongolia, China, but the text is placed above the arms of the Chifeng cross.[79] F. C. Burkitt found the same Syriac text surrounding the Christian cross, but with the addition of the phrase "the living cross", in one of the Syriac manuscripts in the British Museum, as the frontispiece of the Gospel of Luke.[32]

On the other stone block, the cross also has a Baoxianghua pattern, but there are two heart-like shapes extensions at the left and right ends of the cross. It is also mounted on two layers of lotuses, one facing up and one facing down. On the side, it depicts peonies in a basin.[80]

See also

Christianity in Beijing

- List of Major National Historical and Cultural Sites in Beijing

- Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Beijing – the oldest Catholic church in Beijing

- Zhalan Cemetery – a Ming dynasty cemetery in Beijing for Catholic missionaries who died in China

- Holy Saviour's Cathedral – a former Anglican cathedral

- Christian-founded institutions: Peking Union Medical College (est. 1906), Yenching University (1919–1952), Fu Jen Catholic University (est. 1925, later re-established in Taiwan in 1961)

Other West Asian religious sites in China

- Huaisheng Mosque in Guangzhou, built during the 7th century

- Xianshenlou – the sole surviving Zoroastrian building in China, built during the Song dynasty (960–1279)

- Cao'an – a Song dynasty temple originally used by Chinese Manichaeists, now used by Buddhists

Notes

- ^ In English literature, the site is also known as the Temple of the Cross[1][2] or the Monastery of the Cross.[3]

- ^ A caste broadly corresponding to Central Asians in Yuan-dynasty.

- ^ Youzhou and Liaodong are both regions in the northeast of the Tang Empire. Youzhou is the state that contains modern-day Beijing.

- ^ According to Xu's transcription of the record in his 1992 paper, it was the third year of Zhengtong era (1438).[25] However, Shi put the second year of Zhengtong (1437) in his 2000 paper.[40]

- ^ In his 2001 book The Jesus Sutra, the scholar Martin Palmer claimed that the Tang-dynasty Daqin Pagoda near Xi'an is also a Nestorian Christian site. This view is partly based on P. Y. Saeki's analysis in the 20th century. However, other scholars, including Max Deeg and Michael Keevak, disagreed with Palmer's conclusion, citing modern scholarship. The scholar James H. Morris concluded in 2017 that more detailed archaeological analysis of the pagoda's site is needed, and that "there are no proven direct archaeological remains for the presence of Christianity during the Tang period."[55]

- ^ Romanization: ḥwrw lwth wsbrw bh. Pronunciation: ḥur lwātēh w-sabbar bēh.[77]

References

Citations

- ^ Borbone 2006, p. 7.

- ^ a b Marsone 2013, p. 205.

- ^ Nicolini-Zani 2011, p. 356.

- ^ Hofrichter 2006, p. 12.

- ^ Hofrichter 2006, pp. 12–14.

- ^ Mar Aprem Metropolitan 2018, p. 71.

- ^ Tang 2004, p. 78.

- ^ Tang 2004, pp. 78–85.

- ^ Shi 2000, p. 90.

- ^ Tang 2004, p. 91.

- ^ Tang 2004, p. 94.

- ^ Tang 2004, p. 98.

- ^ Tang 2004, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Zhu 1993, p. 200.

- ^ a b Qiu 2002, p. 64.

- ^ a b Wang 2018, p. 317.

- ^ Wang 2018, p. 342.

- ^ Tang & Zhang 2018, p. 88.

- ^ Saeki 1943, p. 507.

- ^ a b Tang 2011a, p. 123.

- ^ Tang 2011a, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Wang 2018, p. 317–319.

- ^ Tang 2011a, p. 120.

- ^ a b Xu 1992, p. 187.

- ^ a b c d e Xu 1992, p. 188.

- ^ Xu 1992, p. 187, 「故干支錯亂 [...] 皆可能是明人所致」 (Thus the errors in the Ganzhi sexagenary cycle [...] were likely made by Ming people)

- ^ Shi 2000, p. 91, 「1215年蒙古军攻下金中都(北京)后,景教即传入北京。北京作为景教的一个大主教区,派驻有大主教」 (After the Mongolians captured the Jin's capital, Zhongdu [Beijing] in 1215, the Church of the East spreaded into Beijing. As a metropolitan see of the Church of the East, Beijing had a metropolitan bishop)

- ^ a b c d Wang 2018, p. 343.

- ^ Tang & Zhang 2018, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Tang 2011b, p. 108.

- ^ Shi 2000, p. 91, 「据史籍记载,当时有一位出生在北京的景教修士拉班·扫马」 (According to historical records, there was a Nestorian monk born in Beijing called Rabban Sauma)

- ^ a b c d Moule 2011, p. 88.

- ^ Shi 2000, p. 92, 「值得注意的是,据记载,拉班·扫马的静修处,距城有一天的路程,在附近的山上有一个山洞,紧靠洞旁有一清泉。其地形地貌与房山十字寺及附近的三盆山极其相似」 (It is notable that, according to records, the retreat of Rabban Sauma was one day's journey from the city. There was a cave on a nearby mountain, and a spring was next to the cave. The terrain described was very similar to the terrain of Cross Temple, Fangshan, and the nearby Sanpen Mountain), referencing Zhu, Qianzhi (1993). 《中国景教》 [Nestorianism in China]. People's Publishing House. ISBN 9787010026268.

- ^ Tang 2011b, p. 108, "The Rabban Sauma mentioned in the History of Yaballaha III came from this monastery in Fangshan".

- ^ Wang 2018, p. 318.

- ^ a b Tang & Zhang 2018, p. 86.

- ^ Wang 2018, p. 328.

- ^ Wang 2018, p. 340.

- ^ Wang 2018, p. 341.

- ^ a b Shi 2000, p. 91.

- ^ Shi 2000, p. 92.

- ^ a b Tang 2011a, p. 118.

- ^ Tang 2011a, p. 121.

- ^ Xu 1992, p. 185, citing 《房山縣十字石刻詳紀》; "A Record of the Cross-carved Stones in Fangshan". Ta Kung Pao, literary supplement no. 195. 1931-10-05.

- ^ Bar Sauma & Markos 1928, Appendix B to the Introduction: The Nestorian Stele at Hsi-An-Fu.

- ^ a b Saeki 1937, p. 430.

- ^ Zhou 2017, p. 47, citing Saeki, P. Y. 1951. The Nestorian Documents and relics in China. The Maruzen Company Ltd., Tokyo..

- ^ Tang 2011a, p. 119, citing Saeki 1943, pp. 500–502.

- ^ a b c d Wang 2018, p. 311.

- ^ Cao 2000, p. 42-43.

- ^ a b Wang 2018, pp. 311–312.

- ^ a b c d Tang 2011a, p. 119.

- ^ Wang 2018, p. 314.

- ^ Shi 2000, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Morris 2017.

- ^ a b c Wang 2018, pp. 310–311.

- ^ Li 2015.

- ^ Wang 2018, p. 310.

- ^ Wang 2018, pp. 339, 341.

- ^ Wang 2018, p. 320.

- ^ a b Tang & Zhang 2018, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Wang 2018, p. 338, 「这一切其实都是为了让“敕赐碑”显得真实,从而提高该寺的规格,并得到信众的支持资助。拨开笼罩在元碑上的敕赐迷雾,元碑记述的寺庙情况应该是基本可信的」 (All of these were done to make the "Royal Stele" more realistic, so to elevate the status of the temple, and to obtain more support from the believers. If we discard the mystery of the "royalty" on the Yuan-era stele, it provides a credible record of the temple)

- ^ Tang 2004, pp. 18, 29.

- ^ Tang 2004, p. 29.

- ^ Tang 2004, p. 19.

- ^ a b Xu 1992, p. 185.

- ^ Tang & Zhang 2018, p. 83.

- ^ a b c Wang 2018, p. 312.

- ^ Tang & Zhang 2018, p. 82.

- ^ a b c d e Xu 1992, p. 184.

- ^ Niu 2007, p. 229.

- ^ Zhou 2017, p. 47, citing Saeki, P. Y. 1951. The Nestorian Documents and relics in China. The Maruzen Company Ltd., Tokyo.

- ^ Moule 2011, p. 86.

- ^ Burkitt 1921, p. 269.

- ^ Tang 2011b, p. 140, "Adoration of the cross and images was another characteristic of the East Syrian traditions in the Far East".

- ^ Borbone 2019, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Borbone 2006, p. 2.

- ^ Borbone 2019, p. 138.

- ^ Xu 1992, pp. 184–185.

Newspapers

- Li, Xue (2015-04-27). 北京十字寺遗址保护面临困境 [The Protection of the Site of the Cross Temple in Beijing Faces Difficulty]. China Culture Daily.

Dissertations

- Zhou, Yixing (2017). Studies on Nestorian Iconology in China and part of Central Asia during the 13th and 14th Centuries (PDF) (PhD thesis). Ca' Foscari University of Venice.

Journal articles

- Borbone, Pier Giorgio (2019). "A "Nestorian" Mirror from Inner Mongolia". Egitto e Vicino Oriente. 2019 (XLII). Pisa University Press: 135–149. doi:10.12871/978883339342112. S2CID 234692204.

- Burkitt, F. C. (1 April 1921). "A New Nestorian Monument in China". The Journal of Theological Studies. XXII (3): 269. doi:10.1093/jts/os-XXII.3.269.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Cao, Xinhua (2000). 房山十字寺的变迁 [History of the Cross Temple at Fangshan]. 中国宗教 [Religions in China]. 2000 (3): 42–43. ISSN 1006-7558.

- Morris, James H. (July 2017). "Rereading the evidence of the earliest Christian communities in East Asia during and prior to the Táng Period". Missiology. 45 (3). SAGE Publications: 235–267. doi:10.1177/0091829616685352.

- Nicolini-Zani, Matteo (2011). "Reviewed Work(s): East Syriac Christianity in Mongol-Yuan China. Orientalia Biblica et Christiana, vol. 18 by Li Tang". China Review International. 18 (3). University of Hawai'i Press: 354–358. doi:10.1353/cri.2011.0078. JSTOR 23733468. S2CID 142980336.

- Qiu, Shusen (2002). 元亡后基督教在中国湮灭的原因 [The Reason of the Annihilation of Christianity after the Overthrown of the Yuan Dynasty in China]. 世界宗教研究 [Studies in World Religions] (in Chinese). 2002 (4): 56–64, 156.

- Shi, Mingpei (March 2000). 略论景教在中国的活动与北京的景教遗迹 [Jing-jiao (Nestorianism) in China and Its Remains in Beijing]. 北京联合大学学报 北京联合大学学报 [Journal of Beijing Union University] (in Chinese). 14 (1): 90–93. doi:10.16255/j.cnki.ldxbz.2000.01.025.

- Tang, Xiaofeng (2011a). 北京房山十字寺的研究及存疑 [Studies and Questions on the Cross Temple, Fangshan, Beijing]. 世界宗教研究 [Studies in World Religions] (in Chinese). 2011 (6): 118–25.

- Wang, Xiaojing (2018). 房山十字寺辽、元二碑与景教关系考 [A Study on the Relationship between the Two Steles from Liao and Yuan Dynasties at the Cross Temple, Beijing, and the Church of the East in China]. 北京史学 [Beijing History] (in Chinese). 2018 (2): 309–43.

- Xu, Pinfang (1992). 北京房山十字寺也里可温石刻 [Yelikewen Stone Carvings at the Cross Temple, Fangshan, Beijing]. 中国文化 [Chinese Culture] (in Chinese). 1992 (7): 184–89.

Book chapters

- Borbone, Pier Giorgio (2006). "Peshitta Ps 34:6 from Syria to China". In W.Th. van Peursen; R.B. ter Haar Romeny (eds.). Text, Translation, and Tradition: Studies on the Peshitta and its Use in the Syriac Tradition. Brill. ISBN 978-90-47-41057-7.

- Hofrichter, Peter L. (2006). "Preface". In Malek, Roman (ed.). Jingjiao: The Church of the East in China and Central Asia. Routledge. ISBN 9781032068237.

- Marsone, Pierre (2013). "When was the Temple of the Cross at Fangshan a "Christian Temple"?". In Tang, Li; Winkler, Dietmar W. (eds.). From the Oxus River to the Chinese Shores: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-643-90329-7.

- Mar Aprem Metropolitan (16 Oct 2018). "The Church of the East in China (Jingjiao)". Yearbook of Chinese Theology 2018. Yearbook of Chinese Theology. Vol. 4. pp. 71–81. doi:10.1163/9789004384972_006. ISBN 978-90-04-38497-2.

- Niu, Ruiji (2007). "Nestorian Inscriptions from China (13th–14th c.)". In Malek, Roman (ed.). Jingjiao: The Church of the East in China and Central Asia. Institut Monumenta Serica. ISBN 3-8050-0534-2.

- Tang, Xiaofeng; Zhang, Yingying (2018). "Fangshan Cross Temple (房山十字寺) in China: Overview, Analysis and Hypotheses". In Huang, Paulos Z. (ed.). Yearbook of Chinese Theology. Vol. 4. pp. 82–94. doi:10.1163/9789004384972_007. ISBN 978-90-04-38497-2.

Books

- Bar Sauma; Markos (1928) [Written during the Yuan dynasty, manuscript found in 1887]. The Monks of Kûblâi Khân, Emperor of China. Translated by E.A. Wallis Budge. London: Religious Tract Society.

- Moule, A. C. (2011) [1930]. Christians in China Before the Year 1550. Beijing: Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-61143-605-1.

- Saeki, P. Y. (1937). The Nestorian Documents and Relics in China. Tokyo: The Academy of Oriental Culture, Tokyo Institute. OCLC 7078566.

- Saeki, Yoshiro (1943). 支那基督敎の硏究〈1〉唐宋時代の支那基督教 [Research on Chinese Christianity, Book I: Chinese Christianity during the Tang and Song dynasties]. 春秋社.

- Tang, Li (2004). A study of the history of Nestorian Christianity in China and its literature in Chinese: together with a new English translation of the Dunhuang Nestorian documents (2nd rev. ed.). Peter Lang. ISBN 3631522746.

- Tang, Li (2011b). East Syriac Christianity in Mongol-Yuan China (12th–14th centuries) (1st ed.). Harrassowitz Verlag. doi:10.2307/j.ctvc16hhv.

- Zhu, Qianzhi (1993). 中国景教 [The Nestorianism of China] (in Chinese). Beijing: Dongfang Press (东方出版社). ISBN 7-5060-0301-5.

Further reading

- Wu, Mengling; Xiong, Ying (2010). 北京地区基督教史迹研究 [Studies on Christian Historical Sites in Beijing] (in Chinese). Wenwu Chuban She (文物出版社).

External links

Media related to Cross Temple at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cross Temple at Wikimedia Commons- Official page of the site of the Cross Temple at Beijing Municipal Cultural Heritage Bureau (北京市文物局)